The Lonesome Club Murder Mystery

True Detective Mysteries, July 1932

By JOSEPH CHOATE, Deputy District Attorney Los Angeles, California

As told to ALBERTA LIVINGSTON

“HAND ME THE BAG!”

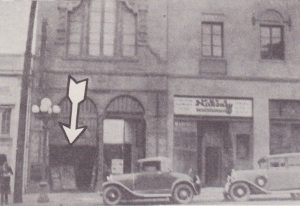

The dance hall at 926M West Seventh Street, Los Angeles, California, where the Lonesome Club held its social affairs. Arrow points to the door-way leading to the clubrooms upstairs

The voice was cultured and calm—but determined—the voice of one who would tolerate no temporizing. Killing would mean nothing to the man behind the mask.

Terrified, Mrs. Melvin Hatch screamed as she handed over the bag containing more than five hundred dollars. The scream attracted her son, who was walking to a friend’s car parked at the curb.He made a flying leap toward the house.

“Oh, Earl, don’t come! He has a gun!” his mother called out. But Earl kept on coming.

When Mrs. hatch realized the terrible thing that might happen, every scintilla of fear left her. Her son was in jeopardy! If she could wrest the gun from the intruder before Earl reached the porch! She grappled with him.

Out of the darkness came a flash of fire—the report of a pistol—the thud of a falling body. Young Hatch lay for a moment, then tried to get up.

“You lie there!”

The tone was not harsh nor high-pitched, but it left no doubt in the mind of the wounded man that the bandit meant business. As he finished speaking, the gunman dashed down the steps, ran diagonally across the lawn and leaped into a waiting automobile.

The Hatch residence at 2149 Echo Park Avenue, scene of a tragedy that startled Los Angeles, and initiated a mystery that was to take three years to solve

Silence! Then a yard filled with talking, excited, frenzied neighbors. Some one had the presence of mind to call the police. A siren soon wailed in the distance. The noise became a veritable scream, then slowly died away as the police ambulance skidded into the curb in front of the Hatch home.

Just as it came to a sighing halt, a white-clad figure swung out of the rear and with practiced ease hooked back the doors and trundled out the wheeled frame into which the stretcher fitted. The wounded man was lifted to the stretcher and ten minutes later lay on the operating table at the Receiving Hospital.

“Gunshot wound of the abdomen—profound shock—possibly fatal.” The nurse at his elbow had completed filling in the chart almost before Doctor Sebastian finished speaking.

Two hours later the patient was transferred to the Osteopathic Hospital where he died at 11 o’clock the following morning. And, with his dying, the Los Angeles Police Department faced an apparently clueless murder—a death that eventually precipitated one of the bitterest battles ever fought in a Los Angeles courtroom.

The victim, Melvin Earl Hatch, Jr., was the son of Doctor and Mrs. Melvin Hatch. The Doctor and his wife owned and operated the Lonesome Club. This club met twice each week at Horn’s Dance Hall, 920 West Seventh Street. These meetings were really public dances, any one being admitted who paid the admission charge.

Doctor Hatch, being well advanced in years and in poor health, spent only about two hours each evening at the club.

Around 10 o’clock Earl Hatch, Jr., would drive over to the dance hall and pick up his father, take him home, then return later for his mother.

Mrs. Hatch, against the advice of friends and relatives, always carried home with her the proceeds of the dances. On Monday night this usually amounted to one hundred dollars, on Friday nights about five hundred.

Charles Freeman, assistant at the dub, and a close friend of the Hatch family having failed in his attempts to discourage this practice, followed the Hatch car home each night. He waited at the curb until the son had put the car in the garage and escorted his mother to the house; then he drove (Earl) Melvin1 to his own home, two blocks away.

On Friday, April 8th, 1927, they followed the usual routine. Doctor Hatch was taken borne by his son about 10:30 p.m. Earl returned and picked up his mother at ten minutes to twelve.

The Hatch bungalow, located at 2149 Echo Park Avenue is built on a hillside. The garage is on the front of the lot opening directly on the street. As they drove into the garage, Earl handed his mother the money hag and also a small laundry bag. He lockedthe garage door and followed her to the porch.

“I can take these things in myself, son. You are tired, so run along home,” said Mrs . Hatch.

Earl, unusually tired, placed the bundles he carried on the banister of the front porch, kissed his mother good-night, and walk ed toward the Freeman car.

Mrs . Hatch tried the front door and found it locked. She looked for the latch-key but it was not in its usual place. The house was in semi-darkness. It had never been that way before. There was just a dim light coming from the bathroom—a night light, which they always kept burning

She peered through a small glass panel in the door. Doctor Hatch was sitting in his chair before the fireplace. But he looked different—downhearted or something—as Mrs. Hatch described it later.

“Daddy, let me in. It is I,” she called out, rattling the door-knob.

He arose and came slowly toward the door. When almost there he straightened up and shouted, “A robber is in the house. He has his gun trained on you!”

Almost instantly the bandit popped up in the doorway directly in front of her with his command:

“Hand me the bag!”

Charles Freeman heard the scream, then the shot, and realized instantly that the long-expected hold-up was being staged. As the bandit fled across the lawn Freeman fired once with a .32 caliber automatic which he carried.

Detectives from the homicide bureau and a finger-print man arrived a few moments after the ambulance. Doctor Hatch told them the tragic story. He stated that as soon as he reached home he put water on the stove to heat. He heard the front doorbell ring and found a rather good looking young man at the door.

“Is Mrs. Hatch at home? I am a friend of hers,” a well-modulated and pleasant voice announced.

“No, she has not arrived. I am expecting…. ” The sentence was never finished. Doctor Hatch found himself looking into the business end of a blue steel automatic.

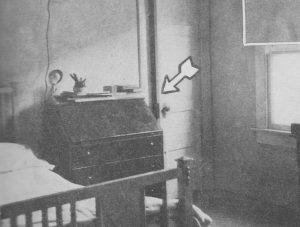

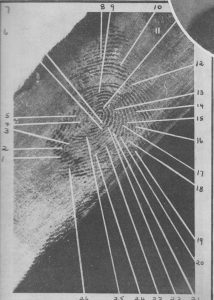

Door of the closet in which the murderer hid. Arrow points to the finger-print he left on the edge of the door, that years later was to trap and convict him

“You old—, you keep absolutely quiet.” The youth marched the old man into the house, shoved him through a bedroom door and into the clothes closet. The key was turned in the lock. Doctor Hatch, ill and frightened, pleaded with his jailer to allow him to come out of the closet and go to bed. The closet door was jerked open and a chair shoved in.

“Stay there quiet for five or ten minutes,” commanded the gunman.

The Doctor could hear the man moving around from one room to another. About fifteen minutes elapsed,

then he again unlocked the closet door.

“Where do you sleep?” he asked.

“On the sleeping porch in the rear,” replied the Doctor.

“Well, you won’t be sleeping there tonight. Lie down on that bed there and face the wall. A sound out of you and it will cost you your life,” he threatened, as he hastily went through the Doctor’s pockets and extracted a wallet containing about forty dollars.

“Now get up and sit down by the fire and act as if nothing unusual had happened,” he commanded. donning the Doctor’s overcoat, he took up a listening post in the closet, his gun trained on the old man at the fireside.

At the risk of his life Doctor Hatch had shouted the warning to his wife!

The Doctor said that to his knowledge he had never seen the bandit before. They had no enemies and knew of no suspects, although he felt sure the man was familiar with all their movement’s, even to the point of knowing the money was carried in a bag, as he had said without hesitation, “Hand me the bag!”

Mrs . Hatch could give no description of the murderer other than “he was taller than I am. I had to look up to him. I couldn’t identify him by his face or by his appearance, but were I ever to hear his voice again, I would recognize it immediately. It was not a shrill voice—it was not a staccato voice—not a voice that faltered—not a voice that would impress. There was no distinguishing mark nor characteristic feature—just a well-modulated voice—but one I will never forget!”

The police discovered that the telephone wires throughout the house had been cut.

While the detectives were questioning Doctor and Mrs. Hatch and Mr. Freeman, Officer F. C. Frederiksen, of the finger-print bureau, went through the usual procedure. He sprinkled a dark powder on the fight woodwork of the closet door where he had found finger-prints, took a small piece of white paper, wrote the words, “Shooting, 4-9-27, 2149 Echo Park Avenue,” thereon and pasted the paper alongside the finger-prints. He then placed the finger-print camera over the prints and the paper, extinguished the light in the bedroom, and snapped the camera.

While it was not absolutely necessary to extinguish the light, Officer Frederiksen did this for the reason that the camera protruded slightly over the edge of the door. A dark area appeared on the photograph of the print when it was developed which later became the subject of much controversy.

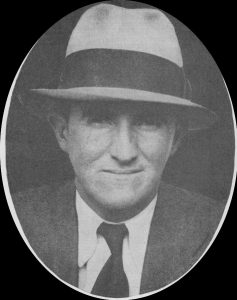

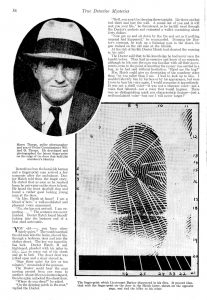

Lieutenant Howard L. Barlow, finger-print expert of the Los Angeles Police Department, whose quick eye and thorough-going knowledge of his subjectsolved this three-year old murder mystery

Unable to find but two prints, one of which was so blurred that it could not be considered evidence by an expert, he returned to the station and removed the plate holder from the camera. He put the plates in his pocket and turned them over to Lieutenant Howard L. Barlow, well-known finger-print expert, at 8 o’clock that morning.

Lieutenant Barlow is one of the twenty-six hundred or more officers of the Los Angeles Police Department and he is a most interesting personality. I consider him one of the greatest authorities on latent finger-prints in the United States. He has acquired this knowledge by many years’ hard work which has been concentrated upon single linger-print identification.

Lieutenant Barlow’s definition of a latent finger-print is, “a Finger-print that is hidden, concealed, invisible, until developed with powder that contrasts in color with the object on which the print is deposited, whereupon it emerges from its latent state and becomes visible.”

As soon as Lieutenant Barlow received the plates front Officer Frederiksen, he took them to the police photographer and had them developed and printed in his presence. This is the way latent finger-prints are handled when found at the scene of a serious crime. Then the expert began the endless checking.

In the meantime the police were rounding up suspects and bringing them in for investigation and possible identification.

Harry Thorpe, police photographer and son of Police Commissioner Wilard G. Thorpe. He developed and photographed the latent finger-print on the edge of the door that held the murderer’s identity

One suspect was found with a gun in his possession. His description tallied with that of the murderer. Doctor and Mrs. Hatch were sent for. After a lengthy conversation, both stated that they felt certain he was not the one. Officers had already eliminated him through finger-prints.

Another man was brought into the case by a Mrs. Siam. floor-lady at the club. He had formerly worked there and during a love quarrel with Mrs. Stam, a gun had been discharged. Mrs. Stam was shot, and her assailant received six months in the county jail.

When questioned regarding the Hatch affair, he furnished an alibi, but admitted that he had made a remark while in jail that there were a couple of old “hens” he was going to get when he was released.

A former ticket-taker at the Lonesome Club had driven Doctor and Mrs. Hatch home many times and was known to be short of money. He had been borrowing from various persons. He was questioned, but released for lack of evidence.

At least six times the Doctor and his wife were called to the detective bureau. Each time Mrs. Hatch declared that the suspect was not the one whose voice she had heard at her home on the night in question.

Then, Doctor Hatch died. The strain had been too great. Soon after, the case was relegated to the file marked, “Unsolved Murders,” and forgotten apparently by all save the finger-print expert.

Lieutenant Barlow has a unique system for filing single finger-prints. Copies of the ten finger-prints of every person arrested for robbery, burglary, receiving stolen property, grand theft and murder, are turned over to him. These are cut into single prints and filed individually. They are classified further as to pattern and ridges. When a single finger-print is found at the scene of a crime that presents sufficient detail to conduct a search, it is taken to this file and identified, provided a duplicate exists.

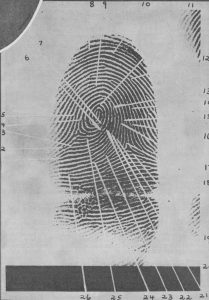

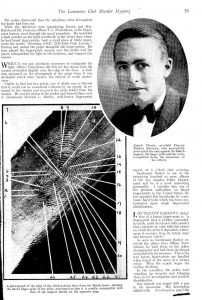

The finger-print which Lieutenant Barlow discovered in his files. It proved identical with the finger-print on the door in the Hatch home, shown on the opposite page (below in this transcript), and tied the killer to his crime

Occasionally Mr. Barlow takes a finger-print from’ some old unsolved crime and searches for it in this file. Following his usual custom, on August 28th. 1930, he took the old print found at the Hatch residence and checked it. Could he believe his eyes? There, right in front of him was an exact duplicate.

A quick search of the records showed that the print belonged to one Percy Eberlee, arrested July 1st, 1930. on a suspicion of robbery charge. A bank messenger had been held up by two bandits and relieved of $2130. One of the bandits, Pierre Satano had been captured fifteen minutes after the holdup. The other had escaped in a stolen car. Through information furnished by Salaam officers surprised Eberlee asleep with a A5 caliber revolver under his pillow.

Eberlee was still in the county jail. Barlow called upon him and informed the prisoner that he had identified his fingerprints in the Hatch home where a murder had been committed in 1927. “Have you ever been in the house located at 2149 Echo Park Avenue, Eberlee?” Barlow questioned.

Eberlee denied that he had ever been in that house or in any other house on Echo Park Avenue.

“There is no question about the identification. Bring in one hundred experts and they will agree with me,” said Barlow, “but we want to see if Mrs. Hatch can identify the suspect’s voice.” So, the next day, Lieutenant Barlow, Detectives Sanderson and Corsini, and Mrs. Hatch visited the jail.

A photograph of the edge of the clothes-closet door from the Hatch home, showing the latent finger-print of the killer, developed so that it is readily comparable with that of the suspect shown on the opposite page (Above in this transcript)

Percy Eberlee and other prisoners were placed in the shadow box behind a screen through which voices could penetrate but faces could not be distinguished. One by one the prisoners spoke the words, “Hand me the bag. You liee there.” When Eberlee’s time came, Mrs. Hatch cried out without hesitation, “That is the man; I could never forget his voice.”

Later, face to face with the suspect, she reiterated her conviction. that he was the murderer of her son. Lieutenant Barlow took a complete set of the suspect’s prints for future use.

On October 2nd, 1930 Eberlee was convicted in superior court on five counts of robbery, and sentenced to San Quentin Prison. In the meantime, after a thorough inquiry, the District Attorney’s office issued a complaint charging him with the murder of Melvin Earl Hatch, Jr. He was taken into Judge Walton Wood’s Court on October 27th, held to answer, and ordered to trial in Judge Marshall McComb’s court on December 3rd.

The case was assigned to me and I have never prosecuted a case which took such a strangle hold upon me as did thisEberlee-Hatch tangle. It was designated as the “Voice Murder” throughout the trial, as the mother’s only memory of the bandit, aside from his shadowy form, was the tone of his voice. The single unblurred finger-print found on the door was the only other bit of evidence linking the prisoner with the murder.

A finger-print and a mother’s memory of how two short sentences were spoken by a strange voice more than three years before were not much upon which to build a murder case, but, because I believe in finger-prints as an absolute means of identification. I went at it tooth and nail.

Joseph Choate, youthful Deputy District Attorney, who successfully prosecuted the case against the Hatch suspect, the finger-print and the voice recognition being the keystones of his efforts

The defense attorney was Joe Ryan. a former Deputy District Attorney with whom I had worked. and who has carved a name for himself in the realm of criminal jurisprudence.

I could just hear Joe Ryan ridiculing the “voice” identification. The entire case would hinge on that single fingerprint. And—Joe Ryan “knew his fingerprints.” I didn’ t doubt that before the trial had ended he would have criminologists throughout the country on their toes, watching with interest his mighty efforts to upset the old standards of finger-print identification.

The case was called Wednesday, December 3rd, 19.30, a t 10 a.m. Both the people a n d the defendant announced themselves as ready. The jury was chosen quickly and the trial was well under way on the second day.

Mrs. Hatch was our first witness. Under careful questioning she related in detail the s tory of the hold-up and murder. Among other things was brought out the fact that since childhood she had studied sound—had taught voice culture in the public schools of Wisconsin—and could identify all common birds by their songs. Attorney Ryan objected strenuously to this line of questioning and his objections were usually sustained.

Just as I expected, he tore into her in his cross-examination, practically forcing her to carry out a dramatic and vivid reenactment of the hold-up and shooting, with Ryan taking the part of the bandit.

Doctor Sebastian testified that he received young hatch at the Hospital shortly after midnight, found a gunshot wound in the abdomen, and two hours later be was transferred to the Osteopathic Hospital.

Doctor Wagner, county autopsy surgeon, testified that he had performed an autopsy, and that, in his opinion. Hatch died of a gunshot wound of the abdomen.

Charles Freeman told of taking an ineffective shot at the bandit as he fled across the lawn.

Shortly after court convened, Miss Mary Ponnay, a friend who had accompanied Mrs. Hatch into the courtroom, informed me that she had seen the defendant at least twice at the Lonesome Club. I placed her on the stand where she testified under oath that during March and April, 1927, she had acted as hostess at the club, and that she had seen Percy Eberlee there on at least two occasions, having talked with him on one occasion.

Percy Eberlee, the mysterious hold up man whose voice made such a deep impression on the mother of the murder victim

Eberlee electrified the court room during her testimony by springing to his feet, his face flushed with rage, shouting: “You lie! You lie! “

Two bailiffs pounced upon him and forced him back into his seat.

Officer F. C. Frederiksen testified regarding the finding of the finger-prints on the door, and to his having kept the plate holders in his possession intact until 8 o’clock in the morning, at which t ime he turned them over to Lieutenant Howard Barlow.

We then called our star witness, Lieutenant Barlow. My first job was to qualify him as an expert. This was not difficult as Barlow has studied every known authority on linger-prints. He went into details, explaining for the benefit of the jury just what a finger-print was; how they were taken, classified and filed; his procedure to prove or disprove an identity ; how photographed at the scene of the crime; and how no two prints had ever been found that were identical unless they originated from the same finger.

To show that the study of finger-prints was a practical science—not mythical—not theoretical, he modestly touched upon the famous Hickman and Preston cases in both of which his knowledge played a big part. He told how the finger-print camera had been turned over to him by Officer Frederiksen; how the police photographer, Harry Thorpe, had developed the films in his presence; and he identified a photograph from the negative taken by Frederiksen.

He explained how he had marked off twenty points of identification between the acknowledged and disputed prints to prove that they were same, but that he could have made a positive identification had only six or seven of the ridge characteristics coincided.

Mr. Ryan then took the witness. He tried in every conceivable way to discredit Barlow and his system: tried to force him to admit that his system was recognized only by himself . He cited Crosskey and Wehde, both convicted criminals, Crosskey claiming his ability to tell ancestry by finger-prints and Wehde claiming that finger-prints could be forged. He dwelt upon the forgery angle, asking Barlow if finger-prints could be forged.

“Anything that can be photographed can be forged, because if you make a photograph of a finger-print or something with intent to deceive, then it is a forgery,” replied Barlow. “But, finger-prints cannot be forged so as to defy detection successfully. They are infallible. They are reliable and furnish a positive proofof identity or non-identity as the case may be, ” he declared.

Failing in this attack, Ryan had Barlow admit that, he had gone through the 230,000 prints on file in the identification bureau of the police department. Ryan then explained to the jury that each of the 230,000 cards bore the imprint of twenty digits, making four million six hundred thousand prints . Of course Mr. Barlow intended to convey the fact, that when comparing a latent print, looking for a record, he compared one finger only.

The fatuous Hall-Mills case was brought up in an effort to show that finger-print experts sometimes disagreed.

The defense tried to trnike Barlow admit that single finger-prints of individuals might be alike although the prints of the ten fingers differed.

This fight between Lieutenant Barlow and Attorney Ryan continued hour after hour, day after day, for three days. What effect it was having upon the jury that listened intently, it was impossible to tell.

Finally, the state rested.

The defense then produced their star witness, Milton Carlson. who gave his profession as Examiner and Photographer of Questioned Documents, and who for the past ten years has been writing articles detrimental to the science of finger-prints.

It was evident from the beginning that Ryan and Carlson had been trying for weeks to think of a possible way to discredit the finger-print system; that Carlson had been placed on the stand to elaborate on Ryan’s revolutionary idea that one finger-print was not enough to convict.

The gist of Carlson’s testimony was that the latent finger-print found at the scene of the crime was too blurred to make an identification. He insinuated that it had been changed and altered and kicked around from pillar to post; that trick photography had been used and that the print, introduced as evidence was but a photograph of a photograph.

Both Lieutenant Barlow and Frederiksen were recalled as rebuttal witnesses.

Mrs. Eberlee was placed on the stand and asked a single question regarding her son’s age.

In summing up, I carefully reviewed the evidence. I attempted to show the jury how the defense had challenged the honesty of police officers Barlow and Frederiksen. I asked if either of these officers would try to fake or concoct a procedure of this type to send a man to prison, perhaps to the gallows? What would be the motive? What would they benefit? Personally, it did not make any difference whether there was a conviction or an acquittal, except that a law had been desecrafed and those who were responsible should be made to suffer. Were they going to believe Barlow, or were they going to believe a man who was receiving compensation for his testimony, and who was not and never had been a finger-print expert’?

Joe Ryan went at the business of summing up for the defense hammer and tongs. He sprang his first surprise argument when he insinuated that Charles Freeman had fired the fatal shot . This was absurd in view of the Autopsy Surgeon’s testimony that the bullet had entered the stomach, whereas Freeman was at all times behind the viceim.

He ridiculed the voice identification inferring that Mrs Hatch believed Percy Eberlee was the man because she believed in Barlow. He also ridiculed Barlow’s connection with the Hickman and Preston cases, calling Barlow the “self -appointed Mussolini of finger-prints, ” then lauded Milton Carlson as a man whose opinions were received the length and breadth of the land. In closing, he asked that the jury bring in a verdict of “not guilty ” on the doctrine of reasonable doubt.

I presume my final summing up was almost as sensational as Ryan’s. I went into full details of the Hickman and Preston cases, asking the jury to give full credence to Mr. Barlow—not his speculation, not his whim, not his hobby, but what he had found through prac ical experience during years of hard work.

I did not plead for the conviction of a man whom I did not think guilty . I was not trying to build a record or a name at the expense of an innocent person. I was not asking them to accept anything new. Finger-print evidence had been used in court many times before. I cited the case of the horrible fire in Ohio State Prison where three hundred persons lost their lives, the bodies being so badly charred that identification was possible only by the use of finger-prints. I then rested the case.

The twelve jurors filed out slowly. Fifty hours later they returned and announced themselves as hopelessly deadlocked, standing seven for conviction and five for acquittal. While disappointed, we were not discouraged. The jury was dismissed and February 10th, 1931, fixed as the date for retrial.

I had lost many hours’ sleep getting my evidence ready for a sure conviction at this second trial. In order that we might produce in court the opinions of other men who were recognized as authorities, we subpoenaed three experts from various parts of the state. This, we felt, would eliminate all doubt in the minds of the jurors as to the identity of the man who had left the finger-print in the Hatch bungalow.

Copies of the disputed and acknowledged prints were to Mr Stone of Sacramento. Mr. Macy. of San Diego, and Mr. Bottorff of San Bernardino. Mr. Stone has had twenty-one years’ experience in finger-print work and is at present connected with the State Bureau of Identification. Mr . Islacy has been in the work sixteen years. and was formerly with the U. S. Navy Department. At present he is with the police department. at San Diego. Mr . Bottorff has had twenty years’ experience and is in the sheriff’s office at San Bernardino.

Each of these men received subpoenas along with the finger-prints. Each made the comparison in his bureau and formed his opinion independently.

Lieutenant Barlow, as in the first case, spent three days on the witness stand. Mr. Ryan tried to tear his testimony to bits. He fired question after question at him, but never once did he falter in his answers. His words rang true. Never was he compelled to correct or modify one statement.

Then followed Mr. Stone, Mr. Macy and Mr. Bottorff. All were qualified as experts. Then each declared: “There isn’t any doubt. it is an absolute identification.”

After we had produced these four well known experts, the court, always seeking impartiality, decided to choose an expert —someone whom I did not know—someone whom Joe Ryan did not know—a man who knew nothing about the case. Who would it be? Away up in the extreme northern part of the state, in Arbuckle, California, he found the man—Hart Schrader, formerly with the State Bureau of Identification, working with Clarence Morrill.

The court instructed his clerk to put in a long distance call for this expert. When the connection was made. Schrader was told to report to the court at his earliest possible convenience. When he arrived in Los Angeles he did just as instructed. He compared samples of the finger-prints. He was shown the door from which the prints had been taken and photographed it. He was then sworn in as a witness.

What would Schrader’s testimony be? Would he testify for the people or the defense?

Schrader first set forth his experience. For sixteen years he had followed the science; for years he had been connected with the state bureau; at present he was in business for himself.

The court asked if in his opinion the finger-prints were the same.

He replied: “In my opinion there is no question but that the finger-prints are the same, and where finger-prints have been used in the civilized world, no two finger-prints have been found that were identical unless made by the same linger.”

“Do you find any points of dissimilarity?” asked the court.

“I have examined these exhibits thoroughly and find none—not one,” said Schrader.

He then said he had examined the door which had been brought into court, and in the area where the finger-print had been photographed he found the identical grain in the wood that appeared in the picture. This showed that the photograph was the original print of the finger and not a photograph of a photograph as claimed by Mr. Carlson.

The defense again called their star witness, Mr. Carlson, who added nothing to the testimony given at the first trial. While he was on the stand the court adjourned for recess.

In my closing arguments I asked but one thing of the jury—to follow the admonition of that immortal English poet, “To thine ownself be true, and it must follow, as the night the day, thou canst not then be false to any man.”

All that remained was the court’s instruction to the jury. Fifteen minutes later they filed out . After twenty-four hours deliberation they filed back.

They announced a verdict of “Guilty” with a recommendation of life imprisonment!

Finger-print identification had successfully withstood one more assault against its gates.

On February 27th, 1931. Percy Eberlee was sentenced to life imprisonment in San Quentin on murder charge, and from five years to life on robbery charges, the sentences to run consecutively.

For a scanned copy of the article click on the page you want below; (The ads around the article are worth peaking at)

A listing of all the articles about the Lonesome Club murder can be found https://hughes-history.com/the-tragic-story-of-the-erl-hatch/

Comments

The Lonesome Club Murder Mystery — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>