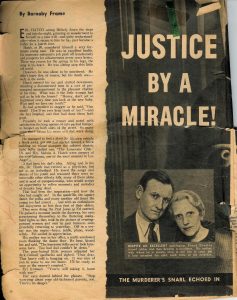

Justice By A Miracle

Inside Detective (Overseas Edition and Normal Edition) January, 1946.

The murderer’s snarl echoed in the Mother’s memory like the voice of doom, until one night….

[Editor’s note: This author has included more information about how the killer was found and about the trial]

By Barnaby Frame

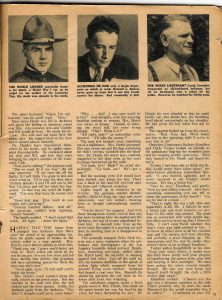

THE WORLD LOOKED especially bright to Erl Hatch. a World War I vet, as he called for his mother at the Lonesome Club. His death was already In the cards.

ERL HATCH swung blithely down the steps and into the night, grinning in wonderment to himself as a man will—and quite understandably—when it recurs to him he has just become a father for a fourth time.

Hatch, at 30, considered himself a very fortunate young man. He was in excellent health, his insurance salesman’s job paid off handsomely and prospects for advancement never were better. There was reason for the spring in his legs, the song in his heart. He was sitting atop this little old world.

However, he was about to be murdered. He didn’t know this, of course, but his death was—well, in the cards.

Hatch entered his car and started downtown, whistling a disconnected tune in a sort of pre-occupied accompaniment to the pleasant rhythm of his tires. What was it the little woman had -said as he left the house ? “Honey, don’t act so frightened every time you look at the new baby. Wait until we have our tenth!”

He had pretended to stagger as he said, “Our tenth! How’ll we ever keep track of ’em!”—and she had laughed, and that had done them both good.

Presently he took a corner and noted with satisfaction the long queues of cars parked bumper to bumper on both sides of the street. So many autos there meant his mom and dad were doing well.

He managed to find a place for his own vehicle a block away, got out and started toward a brick building on whose marquee the colored electric light bulbs spelled out, “The Lonesome Club.” Dr. and Mrs. Melvin A. Hatch were owners of the establishment, one of the most unusual in Los Angeles.

It had been his dad’s idea. Ailing and in his 60s, Dr. Hatch had retired as a physician, but not as an individual. He loved the songs and dances of his youth and reasoned there were in-numerable other elderly folk, many of them alone and in need of companionship, who would accept an opportunity to relive moments and melodies of decades long dead.

That had been the inspiration—and how the idea had caught on! In the quadrille, the square dance, the polka and many another old timer the young too had joined … and with an enthusiasm and enjoyment no less than that of their elders.

They were doing the Paul Jones as Erl entered. He paused a moment inside the doorway, his eyes accustoming themselves to the flattering many-hued lights as they took in the picture of evening-gowned women and men in neat business suits gracefully returning to yesterday. Off in a corner was the music—brass, fiddle, piano, woodwinds. Erl smiled in appreciation.

His mother was in her office, a multi-windowed room flanking the dance foot. He bent, kissed her and said, “The lonesome folks never look lonesome here. Too bad dad couldn’t be down.” The gray-haired little woman adjusted her dark-rimmed spectacles and sighed. “Poor dear, That heavy cold is hanging on. It was nice of you to come to see me home. I’ll be ready as soon as the money’s counted.” Erl frowned. “You’re still taking it home with you?” Her eyes danced behind the glasses. “Stop worrying about your old-fashioned parents, son. There’s no danger.”

“Maybe. But just the same I’d like it better if you put it in a safe here. So much money is a temptation to the wrong kind of people.”

She smiled indulgently. “All right, Erl. If it’ll make you feel better, we’ll install a safe. First of the week. I promise.”

But there was to be no first of the week for Erl Hatch. He helped her with her coat, handed her the paper shopping bag in which she had crammed this Friday night’s particularly large receipts, then escorted her to the street.

She patted his hand. “You’re a good boy, Erl.” There was deep pride in her voice. “Now let’s be on. I’m anxious to get home to dad.”

THE HOUR WAS 11:15 of this chill April 8 night and across town, in the plain but tasteful stucco residence of the Hatches, the elderly retired physician was preparing a cup of tea. He had tried resting on the studio couch, but the ache in his bones persisted and so he had gotten up, eager for the sound of his wife and son driving up. Like Erl, he too had begun to doubt the wisdom of fetching the club’s receipts here.

Absently he watched the steam blossom from the teakettle, unaware that the doorbell had tinkled. But he heard it the second time and glanced up, wondering idly who could be calling at this hour. Violette and his son weren’t due yet.

He went into the, living room and looked at himself in a glass to see that his white hair—what little there was left—was in order. He straightened his heavy wool sweater, brushed a bit of lint from his gray trousers and then, worrying his tie so that it made a more presentable appearance, padded in his leather moccasins to the door.

HELD AT BAY in his home by a gunman seeking a large sum of money. Dr. Melvin Hatch thought only of his wife and son. However, his precaution failed.

In the feeble glow of the porch light- it required several moments for his rheumy eyes to discern that this was no ordinary caller. The young man who stood before him was tall, slender, his eyes a vague shadow beneath the brim of his hat. The face itself was merely a white blob, for a handkerchief had been fastened about it. Dr. Hatch’s stunned gaze dropped to the squat, .glinting object in the other’s hand and he fell back. The gunman lurched across the threshold, nudging shut the door with an elbow.

“Pull down the blinds !” he commanded. His voice was not harsh, but quiet, almost affable. “Don’t be frightened, granddad. I promise not to use any rough stuff .. unless you ask for it. And now that we understand each other, where’s the money ?”

“The money ?” Dr. Hatch found words at last. “But I don’t understand. What .. ?”

“Sure you do, pop. The long green. The money from your dance place. Where do you keep it ?”

“In the bank, of course,” Dr. Hatch replied quickly. “You don’t suppose it would be here ?” “That’s exactly what I do suppose ! You see, I’ve made it my business to know. you hide quite a piece of change around the house before it goes to the bank.” The visitor made a little gesture with the gun. “Better come across. I’m an impatient man.

The 66-year-old physician fumbled with his tie, his mind groping for a way out. Violette and Erl would be arriving soon, and his son’s appearance on the scene augured trouble. Erl would not be one to allow his mother to give up the club’s earnings. He had been through the thick of war in France in 1918 and he would be foolhardy enough to ignore this man’s weapon. . . .

Hatch’s excited brain was not up to the situation. The bandit believed the money was here. And if the doctor explained that his wife was coming home with it and the man waited, what would be the effect upon her? The shock might injure her seriously. She was no longer young. He would need another minute or two to think this out. He said earnestly, “I give you my honor, young man. There is no money here. If there were . .” ”

Never mind the excuses, pop.. have a look-see for myself. Come along.”

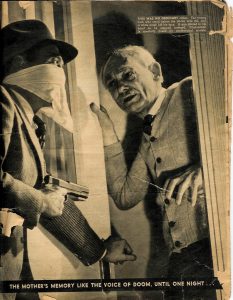

(Dramatization) THIS IS NO ORDINARY CALLER. The young man who stood before the Doctor was tall and a white mask hid his face. A gun glinted in his hand as he stepped forward. (Photograph is specially posed by professional models).

The aged doctor led the way into a bedroom and the gunman motioned to the closet. “Get in there. I don’t want you underfoot while I look around.”

Hatch obeyed. The door started closing on him and he said, “Please be good enough to turn off the burner on the stove. The water for my tea will boil away.”

“Glad to oblige, pop. Sorry the circumstances prevent me from joining you in a cup.”

“Look here, young man,” Dr. Hatch said suddenly. “Your speech is that of an educated individual. Would you please ex-plain how you ever got into this sort …”

“Skip it the robber cut him short, and then closed the door. In the blackness of the closet the white-haired old man was aware for the first time how weak were his limbs and how rapid his heart excitement like this was dangerous to him—more dangerous even than the soft-spoken gunman. He was suddenly faint and he wondered how long his legs would support him, but above all his brain clamored” for an answer to the question, “What shall I do?”

The door opened and the bandit shifted his gun and pushed a chair toward him. “Here, granddad. You’re too old to stand there like a hat rack. Rest yourself.” Something glowed and sparkled in the man’s palm. “I found this thing in a dresser. Brooch. Pretty expensive bauble, isn’t it ?”

Dr. Hatch blinked in the abrupt light and then his lips quivered. “Please don’t take that. My wife values it greatly. You see, I gave it to her.”

The other’ hesitated. “Guess I’m soft-hearted,” was his gruff reply. “Here.”

Once more Hatch was left in darkness and again the feeling of faintness swept over him. Any moment, now, and Violette and Erl would be here. He made his decision. His wife and son came first’, the money last. He rapped hard on the door and it opened almost instantly.

Dr. Hatch’s fears transmitted themselves to his words, and he spoke sonic-what disconnectedly. He explained about his wife and Erl, and how they were bringing the night’s receipts of the Lonesome Club.

“Now you’re talking !” the gunman said.

“But we must do it my way,” the old man quavered. “If we turn out all the lights, Erl will think I’ve gone to bed and won’t come in. I’ll be near the door when Violette unlocks it and I’ll call out to her that I’m there and tell her what has happened. In that way she won’t be frightened. You may then have the money and go.”

“Good deal, pop. How much do you expect she’s carrying ?”

“Several hundred dollars. And all,” the physician couldn’t help injecting, “earned honestly.”

The bandit nodded. “I don’t resent that crack. All right … douse the lights.”

HARDLY HAD THE house been plunged into darkness than there came the sound of an approaching car, then the gentle squeal of brakes as the vehicle rolled to a stop outside. Mrs. Hatch’s voice filtered plainly to their ears. “Thank you, son. I guess you’d better not come in, Dad’s asleep and needs all the rest he can get. Give my love home and tell those darling four kiddies that grandma will have something special for them the next time she’s over.”

“Good night, mom. I’ll wait until you’re inside the house.” Mrs. Hatch’s tread sounded along the walk, echoed on the porch steps. Her key fumbled in the lock and then the bolt clicked and the door opened. Softly, her husband spoke from the darkness, “Violette ? I thought you’d never come home.”

Why .. . dad! I was sure you’d be in bed.” And abruptly, with that amazing intuition curious to women, Mrs. Hatch was aware of danger. Instead of entering, she stood still, her voice rising sharply. “Dad ! What is it?” ”

All right, lady!” an unfamiliar voice directed. “I’ll take the money !”

The next few instants were something out of a nightmare. Mrs. Hatch screamed. Her arm swept out and the bag containing the club’s receipts vanished into the shadows. Dr. Hatch, his worst fears realized, staggered to the door even as his son’s footsteps hammered up the walk.

“Go back, Erl ! Back !” he cried despairingly. “Go back, son! He’s got a gun!”

But the warning, even if it would have been heeded, was given too late. There was a flash of fire and Erl swerved onto the lawn and collapsed, moaning.

Lights leaped up in windows in the vicinity. The gunman snarled unintelligibly, clattered down the steps and stood indecisively over his victim’s twisting form as though contemplating another shot.

“You lie there !” he snapped. And with these incongruous words—words that one (lay were to entrap him—he melted into the darkness, the bag of money abandoned behind him. A moment later from up the street came the sound of a starting car and then its receding hum as it disappeared in the night.

The normally tranquil Echo Park district was a noisy confusion when the ambulance and investigators of the Los Angeles homicide detail arrived. Neighbors, chattering nervously, milled about the Hatch lawn, the majority in sleeping apparel and robes. Just off the walk lay Erl, his features deathlike in the splash of yellow light which streamed from his parents’ living room window. Someone had draped a coat over him. Beneath the sheltering garment the red stain on his lower shirt front was widening.

The ambulance surgeon spoke a brief, gentle word to Mrs. Hatch, who knelt on the grass beside her son, his head in her arms, her tears dampening his face. Dr. Hatch, his eyes clouded so that he could hardly see, was beside her, his trembling hand placed reassuringly on her shoulder. He had given his boy what first aid he could.

The surgeon looked up from his exami-nation. “Bad. Very bad. We’d better get him to the operating table if we’re to save him at all.” Detective Lieutenants Rodney Hamilton and Clyde Tucker looked on silently as the ambulance bearing the wounded man and his weeping mother sped away. Then they turned to Dr. Hatch and heard his story.

“If only I had been able to think clearly, this would never have taken place,” the white-haired physician reproached him-self. “I was excited, agitated, and it never occurred to me Violette would scream. Erl was a brave boy.”

“Sure he was,” Hamilton said gently. “Now try and collect yourself. Isn’t there something outstanding you can tell us about the appearance of this bandit ? You say he had on a mask . . .”

“That is right. He was a tall, thin man apparently in his 30s. I believe he wore a tweed coat and dark trousers—or perhaps it’s the other way around. My mind was so concerned with what might happen when my boy drove up that I observed little. I can’t even ‘recall whether this man’s voice was high pitched or low. I do know he didn’t seem at all the criminal type and I’m certain he’d had schooling and probably a good bringing up. His mannerisms and the way he spoke—they weren’t those of an ordinary hoodlum.”

Tucker pulled thoughtfully at his chin. “From your story, doctor, it would seem this bird knew pretty well your practice of transferring the money from your club and keeping it here overnight. He must have gotten his wires crossed tonight, though. He saw you were home and figured you’d brought the cash ;i little earlier than usual.”

“IF WE CRACK THIS case.” said Detective Lieutenant Rodney Hamilton- “it will be a miracle—and what a miracle!” But this wonder came to pass.

Hamilton nodded. “Chances are this guy was a frequent customer at the club. That’s probably why he wore the mask. Reasoned the doc would remember him if he didn’t.”

Detective Sergeant Fred Frederiksen joined them after making a check of the neighborhood. “Found where this mug parked his car up the street. Woman in the house opposite said the machine had been there some lime—an open job. Another neighbor also saw the car and was sure it’s a Studebaker roadster. No idea what color,’ though, and nobody got a gander at the license numbers.”

They entered the house and Frederiksen, a fingerprint expert, went to work with camel’s hair brush and powder. The bandit, in the relatively short time Dr. Hatch was imprisoned in the closet, had given the house a thorough going over. Drawers were piled out of dressers, their contents scattered over the floor; a desk had been overturned and even mattresses yanked from beds and slit.

Tucker pointed to the telephone in the dining room. The wire had been cut. “This bird didn’t miss any angles.” Hamilton agreed. “Smart as he was, though, he made the fatal mistake of using his gun.”

Dr. Hatch slumped into the chair and sighed. “He can have what he came after and every other penny I possess, if only my son recovers.”

Frederiksen called to them from the living room. “No soap so far. Every place this bird appears to have touched something there’s a smear—prints wiped clean.”

On the door of the closet in which Dr. Hatch had been confined, however, two apparently recent prints of a right index and middle finger came into view under Frederiksen’s deft brush. Dr. Hatch said the masked man had used his right hand—having shifted his weapon to the left—in shutting the door after pushing a chair toward him. Had the marauder bungled here? It did not seem likely.

Frederiksen set up his camera and photographed the pair of prints. He would have been amazed to know that one day his routine piece of evidence gathering would alter the whole concept of California jurisprudence of the admissibility of a fingerprint in weighing a criminal’s destiny!

At the receiving hospital the investigators consulted with the chief surgeon who re-ported that the .32-caliber steel-jacketed automatic slug had penetrated the abdomen and punctured vital organs. Erl Hatch’s chances for survival were very poor.

Hamilton and Tucker next sought out Mrs. Hatch. The woman’s features were tear stained arid heavily lined, but she had refused a sedative and the recommendation she obtain at least a few hours of sleep. She replied to their questions readily, but, like_ her husband, could tell them little.

“The one thing that stands out in my mind is the words this man used after he shot my son. He said, ‘You lie there!’ No uneducated man would have spoken that way under stress. If ever I hear his voice again, no matter how many years from now, I’ll know it.”

Hamilton cast her a gentle word of warning. “Voices, Mrs. Hatch, are deceptive-especially when we must keep in mind that you too were under stress at the time. There will be suspects in this case and we will call on you, but you must be careful in your identifications. An innocent man must not he made to pay for another’s crime.”

You may be certain that he will not,” she responded stoutly. ”I’m a former schoolteacher. I’ve given much attention to music. My ear has been trained to the voice. Believe me – when I say. ‘This is your man,’ you will have the scoundrel responsible for what has happened tonight.”

“You’ve got to hand it to the old lady—she has convictions and ‘sticks by ’em,” Tucker grinned as he and his partner headed for the homicide bureau to make their report. “She’s a scrapper.”

“Just the same, let’s not bank too heavily on what she says,” Hamilton cautioned. “We’ve had experience enough to know that identification of a suspect, even by an eyewitnesses, is a plenty uncertain business at best. And nobody saw the face of the bird who plugged her son. Brother, take my word for it–if we break this case only because Mrs. Hatch remembers a voice, it’ll he a miracle .. , and what a miracle!”

Despite every effort of medical science in his behalf, Erl Hatch died late that morning, widowing the wife who less than two weeks before had borne him his fourth child.

Hamilton and Tucker had completed the preliminary work to which they were assigned and now Detective Lieutenants Joe Miller and Frank Condaffer picked up the hall. The alarm dispatched the night before in connection with the Studebaker roadster had achieved nothing. There seemed little likelihood that the slug removed from young !latch’s body would avail much when put to comparative tests in the crime laboratory. In that year of 1927 the science of firearms identification was still in swaddling clothes.

The investigators paid a call on Detective-Sergeant Howard L. Barlow, chief of the department’s fingerprint division, and found that expert studying a photograph.

Barlow flipped it across his desk toward the visitors. “This is the shot Frederiksen got of the Hatch closet door. The middle fingerprint is excellent but the index finger isn’t worth a darn. Too fuzzy.”

“What does it add up to?” Condaffer asked.

“Not very much .. right now. We still can’t be sure these are the killer’s prints.”

FOR WEEKS LIEUTENANT Frank Condaffer frequented an old-fashioned ballroom, but all he developed was a talent for the polka. However. he watched the fiddler paid.

Condaffer and Miller journeyed to the Echo Park district. As they chatted with the grieving parents they were increasingly aware of the difficulty of their task—indeed, of its virtual futility.

Actually, all they had to proceed on was a single fingerprint which might or might not belong to the killer—that, and an elderly woman’s declaration that she would be able to identify him if she heard him speak.

WHEN THE Lonesome Club reopened several nights later. Condaffer and Miller were on hand, ostensibly as a couple of gentlemen interested in an evening of relaxation. Present also were half a dozen attractive policewomen who accepted endless dancing invitations—but curiously enough —only from men who were tail, slender and possessed of a flair for words. It was a faint hope—that the killer might make his way here, to gloat and revel in his immunity—but the investigators were seizing at any straw. Ego–the desire to play a game such as this–had many a time trapped a slayer.

But after weeks of the ballroom vigil, Condaffer and Miller were forced to admit that all they had discovered was a special talent for the polka.

Headquarters officers meanwhile were conducting a concerted drive for suspects. Dr. and Mrs. Hatch attended numerous showups, studied the men paraded before them and listened to their speech—but shook their heads resignedly when it was over.

ALTHOUGH HE HAD only a single fingerprint on which to work. Howard L. Barlow never gave up hope that it one day would convict the slayer. And eventually it did!”

The detectives haunted Barlow’s fingerprint bureau, not, it is true, with any great expectations. If the killer was without a previous criminal record uncovering his identity through the single print was impossible. Even if he had a record the likelihood of flushing out the one matching print among the thousands in the police files was so remote as to doom the project from the start. Barlow had only just begun the monumental task of reclassifying all prints into single groups, paralleling the work of the Federal Bureau of Investigation in Washington.

However, he was hopeful. “The Hatch murderer may laugh at us—maybe six months, maybe ten years—but he’s playing a sucker’s game. In the end, we’ll get him,” he vowed. “Here’s the way I look at it. This mug staged a killing which was incidental to his real purpose—and that was to rob. All right. He’ll be trying another robbery …. probably already has. And one of the fine days he’ll he nabbed and that’ll be the end of him.”

Weeks and months ran themselves out without a break and the investigation lagged and finally ground to a halt. Barlow alone kept at his assignment—carefully studying each new batch of prints flowing in from the booking office.

Two years passed. Ailing Dr. Hatch, grief weakening his already slipping hold on life, finally carried his heartbreak to the grave. Bent now with a double loss and herself spent and ill, the gray-haired widow insisted she would not die until she had seen justice done. From this one burning determination she drew strength to carry on in her darkening world of sorrow and despair.

A third year unraveled itself. Crimes of violence continued to make the Los Angeles headlines—some more spectacular even than the Hatch murder, now virtually forgotten. And then, on the morning of June 25, 1930 —, three years, two months and 17 days after the brutal affair in the Echo Park district – -a payroll car of the Citizen’s Truck Company was stuck up in full view of no less than 100 Angelenos at Banning and Vignes Streets.

The brazen heist at Banning and Vignes took but a few moments. A sedan slid alongside the moving payroll truck and a man with a gun, stepping nimbly from running hoard to running board, ordered the driver to proceed to less densely thronged Aliso and Jackson Streets [after the 101 was built these streets no longer crossed].

Here the gunman was joined by his confederate at the wheel of the trailing sedan, and together they helped themselves to a $2000 cash payroll the truck was carrying and, returning to their car, made off.

Then, 22 minutes after the holdup a canary yellow roadster containing two men took a corner in East Los Angeles, spun out of control and crashed into the side of a streetcar. The roadster was demolished. The driver, bleeding from head cuts, .staggered from the vehicle and, as passersby milled about, lost himself in the confusion. His companion also attempted to get away. but a sharp-eyed policeman nabbed him.

The roadster passenger—a short, brown-eyed. heavy-jowled man of 29 who identified himself as Pierre Vincent Saleno—was taken to the emergency hospital for treatment of his numerous lacerations and bruises.

Detective Lieutenant Eddie Romero, a veteran investigator with an insatiable curiosity, was dissatisfied with Saleno’s explanation that his friend had fled the scene of accident because of the fear of its ‘consequences. He was even less satisfied when Salem professed not to know the other’s name nor anything about him. Romero looked into the police files, and convinced himself something fishy was afoot when he discovered that Salem, possessed a record of arrests including bootlegging, grand larceny, manslaughter, petty larceny and burglary, dating back to 1923.

The skeptical sleuth began an investigation which soon developed that Saleno’s pal had not only ignored his injuries, but paused long enough in his flight to stick up a nearby pharmacy and steal the druggist’s car.

It was then that Romero began to suspect that Saleno and the fugitive were involved in the payroll robbery. Salem’s companion was a tall man bearing out the general description of the individual who had wielded the gun in that daring exploit.

Romero put in a call for the driver and messenger—victims of the Citizens Truck Company job—and escorted them to the city jail, where Saleno had been transferred after his hospital treatment. The men at once identified the prisoner as the operator of the Ford sedan which had been used in the holdup.

Two days later the Ford itself was found abandoned a mile and a half from the hijacking scene. Romero’s theory was that Saleno and his pal had switched getaway cars here, hopping into the previously planted canary roadster in a clever maneuver to snarl pursuit.

A check of the Ford’s front license (the rear plate had been removed, presumably as a precaution against identification during the stickup) led to a Rudolf Holding in adjacent Huntington Park. Holding, puzzled when the circumstances were explained to him, admitted he had allowed a friend, Percy Eberlee, to borrow the vehicle the morning of the holdup for a two-week vacation trip into the San Bernardino Mountains.

Holding described Eberlee as a gray-eyed, good-looking young man of 23 tall, broad shouldered and well knit. But he was at a loss to say where he lived other than that he frequently visited people named Blossom in suburban Torrance.

By skillful probing Romero located the Blossom home—a rambling ranch type structure with a pair of smaller buildings in the rear—but he made no attempt to question the occupants. Instead, he took up a concealed position and settled down to wait . . . and watch. He was convinced that since Eberlee had abandoned the Ford sedan, he had had no intention of going to the mountains but had deliberately misled the man from whom he had borrowed the vehicle. It was possible, then that the fugitive was here. The place would make an excellent hideaway.

Twice that day Romero observed a woman leave the main house and make her way to one of the rear buildings. He would have attached no great significance to this were it not that on each occasion she carried something which he was convinced, by the manner of it’s handling, was food.

The detective put in a call to headquarters and late that night two carloads of policemen joined him at a rendezvous near the house. Their guns drawn, the raiding party broke into the rear building.

There they found their quarry, too drowsy with sleep and too stunned by the suddenness of the said to offer resistance. That he might have been dangerous was quite evident, for nestling beneath his pillow beside a thick wad of banknotes was a .45-caliber revolver, every chamber loaded.

Eberlee was brought into Los Angeles, where later that morning he was identified by the two victims as Saleno’s partner in the payroll stickup. This he sullenly charged was a frame-up. Nor would he admit his guilt when he was accused by the druggist of the latter’s holdup following the streetcar accident. The records themselves revealed Eberlee’s use of a half-dozen aliases, although his encounters with the law were not numerous. At 17 he had been fetched into court on charges of grand larceny and resisting an officer and been sent off to the Preston reformatory, emerging the following year. There were a couple of other notations on the blotter, including a San Francisco robbery arrest in 1928 for which he was never brought to trial.

Romero and Detective Lieutenants Aldo Corsini and Leroy Sanderson, assigned to rounding up further evidence against the two prisoners, experienced little difficulty in locating enough to tie them to several additional holdups. The men were arraigned and ordered held for trial and it was then that the tireless Barlow, going over Eberlee’s criminal file, made the discovery which so long ago he had prophesied would come. Ebertee’s right middle fingerprint and that taken from the Hatch bedroom door were the same! The Hatch murder had been broken at last!

Barlow placed his scientific evidence on Captain Bean’s desk and the homicide chief summoned Condaffer and Sanderson.

“This is great stuff,” Bean admitted, but we’ve got to face an important fact—we’ll need more than just this single matching print and Eberlee’s past record of banditry to nail him on a murder rap. Eberlee is a cagy bird, as he’s already shown. He’s a smooth talker and makes a good appearance and he’s bound to have an effect on a jury. He can claim he knew Erl Hatch and was in the home of Erl’s parents and that’s how his print got there. Or maybe he’ll pick up a smart attorney who’ll insist the bedroom print picture is a fake—and you know how a jury may react to that. People aren’t yet convinced that fingerprinting is an exact science and here to stay.”

Condaffer nodded. “What have you got in mind, cap?”

Bean thought a moment. “If Mrs. Hatch can identify this bird we’ll have something with teeth in it. The question is, can she? She’s a sick old lady, and three years . . .”

Sanderson, himself slated eventually to become chief of the homicide bureau, spoke up. “My recollection is that Mrs. Hatch was positive she’d never forget the voice of the mug who shot her son. Why don’t we stage a voice showup—put Eberlee in a line with a couple of dozen other birds and have each repeat the words she heard that night. I was up to see how she was getting along the other day and, while her sight’s poor, there’s nothing wrong with her hearing.”

Condaffer sighed. “I was convinced, once, that that was the way we’d put the finger on the guy, but now I’m wondering how such testimony will stand up in a courtroom. Any mouthpiece would claim the old lady’s too sick to make a competent witness.”

“Not if she picks Eberlee from a couple of dozen men,” Sanderson put in warmly. “Remember! We already have the finger-print evidence that he’s the killer.”

“We’ve nothing to lose in trying,” Bean agreed. “Fetch Mrs.. Hatch—that is, if she’s able to make it tonight, . .”

Sanderson and Condaffer found the ailing widow eager to aid them.

“It’s all I’ve lived for,” she declared brokenly. “The man who murdered my boy. also sent my husband to his grave. I want to see him get what he deserves.” They helped her into her coat and to their waiting car. Everything was in readiness at the First and Hill station downtown. The showup box, a bare stage like room enclosed by a ceiling-high screen impenetrable to the gaze of those inside but no barrier to anyone in the audience, was brightly lighted. Twenty-eight men—the majority prisoners, the remainder detectives and all of a build similar to Eberlee’s—were in the boxlike affair. Sanderson led Mrs. Hatch to a chair near the screen, but she refused it.

“I’ll stand,” she said firmly, staring sharply ahead of her. She touched Sanderson’s arm. “I-1 really can’t – see any of them. It’s all a blur. I don’t want to see them, anyway. Please have the lights turned off. My hearing’s more keen that way.”‘

Sanderson gave the order and all illumination was snapped off.

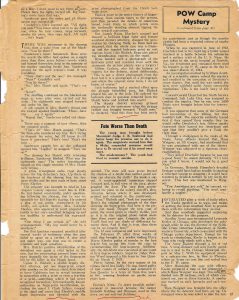

“THAT’S THE MAN! He murdered my boy!” After three years Mrs. Violette Hatch listened to the voices of 18 men and without hesitation picked out one of them. Her identification was correct.

Condaffer’s voice boomed out. “All right, you men ! You know what you’re to do. Each one, when his turn comes, steps forward, speaks his piece, then steps back. All right … let’s begin.”

THERE WAS movement in the showup box, then a voice from out of the black-ness. “You lie there!”

Sanderson’s heart hammered. Here were the words the killer had spoken on a night more than three years before—words which had burned themselves deep in the memory of the mother standing beside him. Sanderson groped for the aged woman’s hand. It was trembling,

“That—that’s not the one,” she managed.

“Next!” Condaffer said.

“You lie there !”

“No,” Mrs. Hatch said again. ‘That’s not it.” “Next !”

The shuffling continued on the blacked-out stage as voice after voice carried out the order. The eighteenth man stepped forward and spoke his line.

A sob caught in Mrs. Hatch’s throat and she swayed against Sanderson. “Have—have him …say it again.”

“Repeat that,” Sanderson called out sharply.

There ‘was a moment of taut silence, then the repeated words.

“That’s it !” Mrs. Hatch gasped. “That’s the man who murdered my boy. He’s trying to- disguise his voice, but I’d know it—I’d know it anywhere! That’s him! That’s the man.. .”

Sanderson caught her as she collapsed against him. “Lights!” he snapped. “Turn ’em on!” –

The showup box blazed with returning brilliance. Sanderson blinked. Who was the eighteenth man? The entire investigation hinged on this single moment. If Mrs. Hatch were wrong. . . .

A grim, triumphant smile crept slowly across the big detective’s face. Up there in the forefront of the showup box, his features chalky and his eyes coals of hate, stood Percy Eberlee.

DESPITE AN EXCELLENT upbringing, Percy Eberlee turned robber and then became a murderer. His mother, with whom he is shown. tried to aid him in court, but a jury accepted the cold, hard facts of the evidence.

The prisoner was brought to trial in Los Angeles County superior court late in 1930. He had denied consistently, under questioning following the showup, that he was responsible for Erl Hatch’s slaying. He entered a plea of not guilty, championed by his lovely, soft-spoken mother, Mrs. Lorraine Eberlee, who appeared in court prepared to testify to her son’s excellent bringing up and her inability to understand his waywardness.

“One thing I am certain of,” she told newspapermen. “My boy could never be a murderer.”

But that question remained unsettled after several weeks of testimony when the jury failed to agree on a verdict. A new trial got under way—one that was to create a scientific and legal sensation.

Mrs. Hatch’s positive identification of the defendant was again a vital factor in the case, but the prosecution pressed home even more doggedly the factor of the fingerprint left by the killer in the Hatch home.

Ugene U. Blalock, a skillful deputy district attorney, put one fingerprint expert after another on the witness stand, determined to force California law to accept testimony in connection with a print or even a fraction of a print—something which it had never recognized heretofore. Internationally known [authorities] on fingerprint identification, including the noted J. Clark Sellers, trooped to the stand and swore that Eberlee’s middle finger impression was identical with the print photographed from the bedroom door.

Blalock wove in the entire history of finger-printing, from ancient times to the present, and then paraded the details of numerous famed court trials -in which prints were the irrefutable deciding element tipping the scales toward conviction.

But Joseph Ryan, Eberlee’s counsel and himself a brilliant legal light and former assistant district attorney, stunned the prosecution by charging flatly, as Bean had anticipated, that the whole case was a frame-up and the reputed bedroom print an outrageous fraud. Like Blalock, Ryan also placed top identification experts on the stand.

Ryan handed each a photograph of the bedroom print and received from each the statement the picture plainly was a forgery!

Milton Carlson, who led the battery of experts for the defense, stated deliberately, “This is not a direct photograph from the door but it is a photograph of a photograph, and where the original came from, I do not know, of course.”

Such testimony had a marked effect upon the already befuddled jury, but Blalock played his ace in the hole. He ordered the bedroom door in question removed from the Hatch home’ and fetched into court!

The deputy district attorney grinned pleasantly at the veniremen [a slang term for jurymen] when the strange exhibit was brought forward. “You’ll note,” He declared, “that this door has been newly painted. The state will now prove beyond the shadow of a doubt that neither paint nor time can obscure the truth.” He made a signal. A court-appointed cameraman stepped forward and, in full view of the jury, photographed the door. The jury then accompanied the plate to the county sheriff’s identification bureau where it was developed, printed and returned to the courtroom.

“Now,” Blalock said, “look for yourselves. Here’s the original photograph of the door showing the fingerprint. And here is the picture just made. Despite the new coat of paint, the wood grain is clearly visible, just as it is in the original photo taken more than three years ago, Compare the grains. You’ll find not one shade of difference between them. And if that is true, then there can be no forgery here!”

The 12 men compared and were impressed.

On February 27, after three weeks of trial, they brought in a verdict finding Percy Harry Eberlee guilty of murder in the first degree but saving him from the rope by recommending life imprisonment. Additionally, the defendant was convicted of one count of first degree robbery. Superior Judge Walton Wood imposed a life term in San Quentin on March 7, 1931.

Pierre Saleno, by the very nature of his crimes, fared less badly. He was found guilty of four counts of robbery and sentenced to San Quentin to a term of from five years to life, winning freedom on parole seven years later.

[ORIGINAL] EDTTOR’S NOTE: To spare possible embarrassment to innocent persons, the names Rudolph Holding and Blossom, used in this story, are not real but fictitious.

A listing of all the articles about the Lonesome Club Murder that I have found can be found here.

Scans of the original article from the overseas edition for the armed forces. The edition for the US market had less articles, but this article is identical in both.

Comments

Justice By A Miracle — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>