The Voice From The Shadow Box

The Voice From The Shadow Box

The baffling mystery of a strange killer and the amazing trap.

Startling Detective Adventure, August 1931

Out of the darkness loomed a phantom gunman, intent on robbery. There was a struggle, a shot—and Los Angeles police faced a baffling murder mystery. For three years a Fingerprint lay useless in the files — then a clever police lieutenant and a bereaved mother with a memory for voices brought the ruthless slayer to justice. Again, the law won.

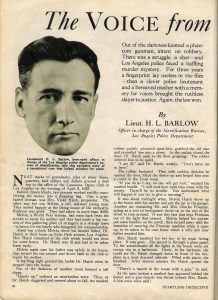

Lieutenant H . L . Barlow, keen-eyed officer in charge of the Los Angeles police department’s bureau of identification, tells this exclusive story of a sensational case that balked solution for years

By Lieut. H. L. BARLOW

Officer in charge of the Identification Bureau, Los Angeles Police Department

Neat stacks of greenbacks, piles of silver dimes, quarters, half dollars and dollars covered a desktop in the office of the Lonesome Dance Club in Los Angeles on the evening of April 9, 1927.

Behind drawn blinds, two persons worked swiftly transferring the money into a shopping bag. One, a grayhaired woman, was Mrs. Violet Hatch, proprietor. The other was her son Melvin [Editors note: His full name was Erl Melvin Hatch, the family called him Erl, but for some reason the author referred to him as Melvin], a tall, stalwart young man. They smiled happily at the lilting music of the orchestra. Business was good. They had taken in more than $400.

Melvin, a World War veteran, had come back from the service to assist his mother and they had made a big success of this gathering place of strangers in a strange town —a haven for the lonely who hungered for companionship.

About ten o’clock Melvin drove his invalid father, Dr. Hatch. to their home on Echo Park avenue, Los Angeles. Mrs. Hatch remained at the club which would not close for some hours. Hatch was ill and had to be taken home early.

Melvin made sure his father was safely in the house, then turned his car around and drove back to the club to

rejoin his mother.

A startling sight greeted the feeble Dr. Hatch when he stepped into the house.

Out of the darkness of another room loomed a tall shape.

“Hands up,” ordered an emotionless voice. Then, as Dr. Hatch staggered and seemed about to fall, the masked

robber quickly advanced upon him, grabbed the old man and propelled him into a closet. As the outlaw closed the

door, Dr. Hatch sank to the floor groaning. The robber ordered him to be quiet.

“I am ill,” said Dr. Hatch, weakly. ” Don’t leave me in here.” The robber hesitated. Then with sudden decision he opened the door, lifted the doctor up and helped him onto a couch in the front room.

“If you do as I say, no one will get hurt,” warned the masked bandit. “I will wait here until they come with the money. There’ ll be no trouble. You understand what will happen if you try to give a warning.”

It was about midnight when Melvin Hatch drove up to the house with his mother and put the car in the garage. Another car containing Mr. and Mrs. Charles Freeman, acting as a sort of bodyguard, drove on to the end of the street to turn around. It was this fact that kept Freeman out of the fight that ensued. Melvin helped his mother put some bundles on the porch ; then turned away with the intention of entering the Freeman machine when it came up, to be taken to his own home where a wife and four

babies awaited him. [Editor Note: There were four children. a boy of 8, a girl of 5 (my Mother), a boy of 2 and a new born girl]

Mrs. Hatch fumbled for her key in its usual hiding place. It was gone. She peered in through a glass panel. To her astonishment all the lights in the house were out except one in a bathroom. Dimly , in the darkness, she could see Dr. Hatch slumped down in front of the fireplace in a most dejected attitude. Filled with alarm, she

knocked. After several minutes Dr. Hatch opened the door.

“There’s a bandit in the house with a gun,” he said.

At the same instant a masked face appeared behind the doctor and a gun muzzle was thrust toward Mrs. Hatch. A low even voice said: “Hand me the bag!” Cold eyes were on the shopping bag of money.

Mrs. Hatch was stunned. Automatically she held out the shopping bag containing the money, more than $400. For a split second she seemed to be choking. Then came the reaction. A scream burst from her.

Hardly had the shriek left her throat before she regretted it. She heard her son call out, knew that he was coming to her help and a new and awful fear assailed her. Melvin would be shot! She knew her son’s courage.

“Oh, don’t come !” she cried. “He has a gun !” Her words trailed off in a terrified shriek.

Reason left her. The masked face and the bandit’s gun swam dizzily before her eyes. She found herself strangely unafraid of that gun. Now only one mad im-pulse filled her. She must save her boy.

She sprang at the marauder, clawing for the hand that held the weapon. The bandit took a startled backward step. He jerked his gun hand behind him and fought the frantic mother off with the other.

Soldier to the end, Melvin Hatch charged straight at the gun of the bandit who was grappling with his mother. A slug in the abdomen killed him.

Before her burning eyes Mrs. Hatch saw the gunman swing his revolver high until it aimed over her shoulder. She heard her son shouting behind her; heard his feet thud on the porch. A prayer was on her lips

Flame spurted from the six shooter. She turned around. Everything went black before her eyes. Her son Melvin-lay writhing on the porch. As she staggered toward her mortally wounded boy she was conscious of the bandit rushing past her and heard his distinct words, spoken in an even, cultivated voice:

“Lie down there.”

The gunman rushed past the wounded man, ran to a car at the curb and raced away. Charles Freeman jumped out of his machine and fired at the bobbing red tail light but the bandit’s roadster turned a corner and disappeared. No one caught the license number of his machine and the handkerchief mask had concealed his face. His description was that of thousands of other young men in the city, five feet ten inches tall, weight 160 pounds, about twenty-five years of age. He was dressed in Dr. Hatch’s long overcoat and cap, which he stole, when he escaped. Apparently he had made a clean getaway.

Melvin was rushed to the receiving hospital. He died the next day. Within half an hour [of the shooting] Police Sergeant Frederickson of the fingerprint bureau and Officers Hamilton and Clyde Tucker were on the scene. Dr. Hatch was in a state of collapse. Mrs. Hatch was frantic. The presence of Melvin’s widow and his four little children added to the sadness of the scene.

Questioning by the police produced practically no clues.

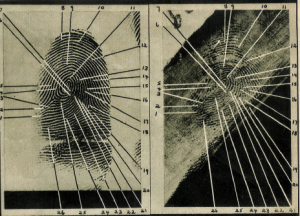

The search for the murderer appeared hopeless. But Sergeant Frederickson persisted. He had Dr. Hatch point out everything that the bandit could have touched in a search for fingerprints. There were none. At last he came to the door of the closet where the outlaw had first imprisoned Dr. Hatch. The door was white. The finger-print man dusted dark powder over it. Just above the knob appeared some smudges left by the bandit’s fingers. Two of the latents were good, but they were only single imprints of the right index finger.

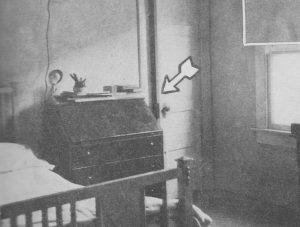

Arrow points to the spot on the closet door where police found a fingerprint of the slayer. It was into this closet that Dr. Hatch was shoved by the ruthless masked bandit.

Sergeant Frederickson pasted a label just above this latent. It gave the address, date and the word “shooting.” Quickly he adjusted his camera and photographed the latent and the label which identified it. The plate never left Frederickson’s legal custody until it was turned over to me, as head of the fingerprint bureau, for development and printing in the presence of witnesses.

In a great many police departments a single print is without value. Most identification records require the imprint of all ten digits. But for the fact that the Los Angeles police department had installed a single finger-print file, our evidence would have been next to useless. Scotland Yard, Berkeley, Calif., and Wichita, Kansas, are the only other places having effective single fingerprint files, that I recall. I classified the print as W3C4 and searched the single fingerprint files for its duplicate without result. Apparently the print of Melvin Hatch’s slayer was not on file with us. In code the W meant a whorl; the 3 indicated the core formation, a circular spiral to the right ; the C meant the inclination sloping to the left; and the 4 the code indicated the count between the core and the nearest delta.

This lone pattern was placed in a file of wanted men future reference. Its whorls, ridges and deltas looker strangely harmless, yet they were destined to play a vita part in the drama that followed.

Meanwhile every other means was being used to identify the murderer. Dr. and Mrs. Hatch spent hours at headquarters looking at the “mugs” of holdup men whose records were in our files. Dr. Hatch picked out several that had the general appearance of the robber but could not make any positive identification.

The Hatch home on Echo Park ave-nue, Los Angeles, on the porch of which the fatal shooting occurred.

Attendants at the Lonesome Club were questioned. It was evident that the robber had spied out his victims’ habits and methods of handling the cash. One visitor to the club was arrested but had to be released.

A roundup of suspicious characters was staged. The usual riff-raff was taken and either released, vagged or held on some rap, but among these were a few gunmen who might have done the job. The question was : How could we identify the robber after we got him? None of the victims had seen his face.

Detective L. E. Sanderson and I interviewed Mrs. Hatch. She was ill from the ordeal. She had seen her son shot down before her very eyes. Her husband was in a state of collapse. But her will was indomitable.

“I’ll do anything to find the man that killed my boy,” she said. She came to headquarters time after time on false clues. She never failed us.

“We have some suspects,” I told her, “but how can you identify them when the robber’s face was masked! How can you be sure?”

Her answer was prompt and spirited. “I would know him anywhere. I would know his voice.”

I exchanged glances with Detective Sanderson. Each of us was thinking the same thing. The identification of a voice would be too flimsy. No jury would convict on it. We explained this to her, but she came hack with a surprising answer.

“But I can qualify as an expert on voices,” she said. “I was a music teacher for years. I know voices. I can distinguish the finest variation in tones. The robber’s voice would be easy to identify. It was finely modulated, cultivated, correct. He was an educated man. I recall the last words he spoke to my son. He told him to “Lie down,’ not lay down’ as an ignorant person would have done.”

She actually convinced us, two hard-boiled police officers, that she could identify a man by his voice and put it over on a jury. Frisco Pete (I am using a fictitious name), picked up in the dragnet, somewhat answered the description of the bandit. He was a gunman. We decided to try her test on him.

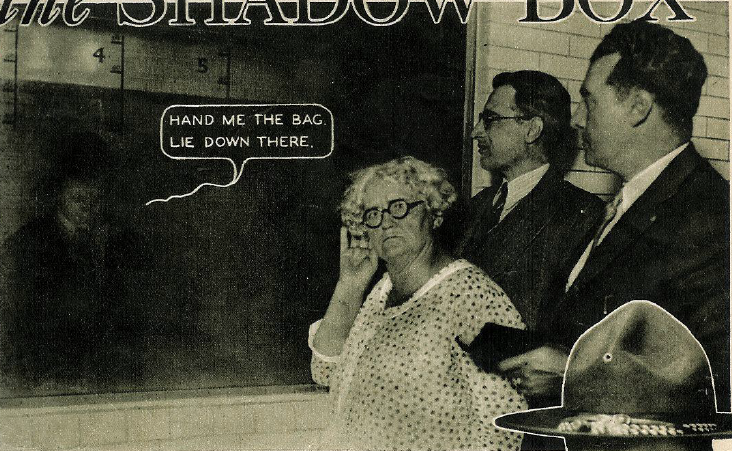

It was a dramatic moment when we took Mrs. Hatch into the darkened room to let her see the first suspects appear on the platform in the illuminated shadow box behind a fine screen. A police shadow box is simply a sort of screened cage where the prisoner stands blinded 11, bright lights which prevent him from seeing the police officers and others who are sitting or standing in the dark-ened room watching him in an effort to identify him. By the use of it, victims of outlaws can appear and scrutinize suspects without themselves being seen and possibly made the subject of retaliation.

Mrs. Violet Hatch, mother of the murder victim, Lieut. Barlow and Detective L. E. Sanderson listen to “the shadow” as he repeats words spoken by the bandit-lciller. Is it the slayer’s voice?

I was standing beside Mrs. Hatch when Frisco Pete entered the shadow box. All his features were sharply outlined by the glaring lights. The gray-haired mother studied him long and earnestly and then shook her head. She could not recognize him. Then came a tense moment. The suspect was made to repeat the words spoken by the murderer at the Hatch home during the robbery. ”

Hand me the bag,” he said. And after a moment, “Lie down there.”

“That is not the man,” whispered Mrs. Hatch, promptly. “That is not his voice.”

Again and again the process was later repeated with other suspects. It was a terrible ordeal but the bereaved mother continued to stand up under it. Occasionally Dr. Hatch accompanied her. Man after man passed before them; but none could be identified.

Time passed. The search seemed hopeless. But Mrs. Hatch never gave up the hope of capturing the man who had slain her son. She was imbued by the same fire and determination that had caused her to fling herself upon the gunman. Again and again she went through the or-deal at the shadow box. Always the suspect was made to say those words; always Mrs. Hatch said it was not the man.

Mileaway Thomas, a noted gunman, was shot in a fight with the police. Dr. and Mrs. Hatch submitted to the terrible ordeal of looking at the corpse. “It might be he,” said Mrs. Hatch. “If only I could hear him speak. But he is dead.” Was Mileaway Thomas the man? Dr. Hatch said he was too large. But many thought Thomas was the killer and considered the case closed. Dr. Hatch died shortly after this.

Life consists of seemingly unrelated incidents that sometimes surprises us by tying in to make a perfect pattern. Melvin Hatch was murdered about midnight April 9, 1927. Three years passed. Everyone except Mrs. Hatch and a few interested men in the police department had forgotten the murder and given up all hope of capturing the criminal.

But it is more than just a slogan to say that the American police as an institution never sleep. They never stop until they get their man. The processes have been re-duced to a stage where they are automatic. It is regular routine in all good police departments to search the files continually for the identification of wanted men.

On June 25, 1930, a bank messenger guard, delivering money to the Citizens Truck Company, was held up and robbed of $2,130 at First and Vignes streets, Los Angeles. A few blocks from the scene the police found a dazed man in the wreckage of a car. He said his name was Soleno and claimed he was a holdup victim. But when he refused to give his address and the car proved to be stolen, he was held.

On clues from this lead the police raided a Wilmington (Cal.) house July 2, 1930, surprised a husky young man in bed and stuck him up before he could grab the .45 caliber automatic under his pillow. He had $230 in his possession. Identified as Percy Eberlee, a robber, he was quickly convicted on four counts and sentenced to prison.

At the left is a fingerprint of the murder suspect, taken by Los Angeles police, while at the right is the single smudge taken from a closet door in the Hatch home after the fatal shooting. For purposes of comparison Lieutenant Barlow has marked the points of similarity.

What could be more remote from the three-year-old killing of Melvin Hatch? Eberlee was taken in July. In August I was making searches of old unsolved crimes. I began looking for the duplicate of that right index finger, W3C4. I found it on Eberlee’s card. A clue at last! We immediately checked up and then charged. Eberlee with the crime.

The big question now was: Would Mrs. Hatch confirm us?

There was never a more dramatic mo-ment in police annals than when Mrs. Hatch gazed at Percy Eberlee through the screen of the shadow box and waited for him to speak.

Eberlee was the right build and age.His right index fingerprint was the same as that found on the door of the closet at the scene of the crime. But we told Mrs. Hatch nothing about that.

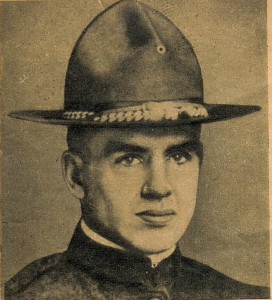

Coolness, daring and intelligence are written on the face of this man who played a major part in the shadow box drama. But a single fingerprint and seven spoken words betrayed him.

Eberlee was cool-voiced and had an iron nerve. When we told him what to say he must have known he was at the end of his rope, yet he never turned a hair. He could have refused to repeat the words spoken at the time of the Hatch killing but he did not. Calmly, unemotionally he said:

“Hand me the bag.” And after a moment, “Lie down there.”

Mrs. Hatch staggered. I steadied her. She choked. We needed no answer. She said nothing until we were out of there. Then the words burst from her lips.

“That is the man,” she cried. “I would know that voice anywhere. He killed my son.” Then she broke down and wept.

We had our man. The next problem was to get a conviction on the strangest and most startling evidence ever presented to a jury, to convict a man on a voice from the shadow box. It didn’t seem possible.

Facing Gangster Threats

The underworld got back of Eberlee.

Mrs. Hatch was threatened. She was actually held up and robbed before the trial. Dr. Hatch, the other eye witness, was dead. But we took hope when a hostess at the Lonesome Club, identified Eberlee as a visitor at the dance hall. He had been standing among the wall flowers. She asked him if he wished to dance but he only smiled and shook his head, she told us. This con-firmed our conviction that the robber had lobked over the ground before committing the deed.

At the trial, which began December 3, Eberlee created a sensation by leaping to his feet and hurling the lie at this witness when she said he had visited the Lonesome Club. It was a bitter battle. I was examined and cross-examined on the science of fingerprinting. The de-fense denied that I could make an iden-tification from a single print. They ridiculed the idea that Mrs. Hatch could identify a voice. On December 13 the jury disagreed, standing seven to five for conviction and the judge ordered a second trial.

Before the new hearing started, Mrs. Hatch was again threatened and held up and robbed. It became more and more evident that the underworld was behind Eberlee. Many a person would have “caved in” from all this pressure brought to bear but not Mrs.. Hatch. She stuck to her guns. Detectives were assigned toguard her. The police learned that gangster friends of. Eberlee sat in the courtroom during the second trial near prosecution witnesses, listening to their conversations.

The second trial became a battle royal. It centered around the fact that the jury was being asked to convict a man on single fingerprint identification. The very principles of the science were attacked. It was pointed out that never before had a conviction been obtained for murder on such evidence. History was being made and it was taken down in transcripts that filled volumes. On March 3, 1931, after the jury had brought in a verdict of guilty, Superior-Judge Wood sentenced Eberlee to life imprisonment at San Quentin.

For three years, for thirty-six long months, an unidentified whorl pattern of a man’s right index finger lay useless in our files. Then with startling suddenness it was brought to life by the operation of the tireless, machine-like system of police identification and pointed an accusing finger at the murderer.

A smudge on a closet door and the cultivated voice of an educated gunman issuing from a police shadow box proved the downfall of a clever crook. The shadow box provided the sensation of the case but it was the little fingerprint that first identified the man.

A listing of all the articles about the Lonesome Club Murder that I have found can be found here.

Scans of the original article. The cover page has not been located.

Comments

The Voice From The Shadow Box — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>