Alice Marsh – Oral History

The Armenian Genocide – Nana’s Oral History Tapes

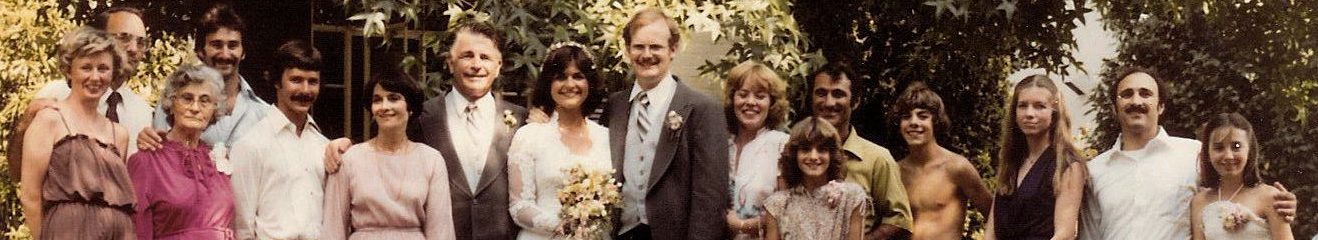

Note: This article was written by Jenee Hughes (My Daughter) for a class at Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo, CA. I have only corrected the spelling of Nana’s birth first name and added photos. Nana is the term that all her grand children called her. I was fortunate to get to know Nana after I married Gayle in 1981. Gayle and I attended Lake Avenue Congregational Church where Nana has been attending since she arrived in Pasadena in December 1920. I miss the little old lady from Pasadena … and her AMC Gremlin.

Jenee’s article follows. The original version is on her website.

|

My great grandmother on my Mom’s side, Alice Marsh (nee Aroosaig Samercashian), lived through the Armenian genocides in the Ottoman Empire, from 1906 to 1919. She died when I was still an infant, but I have been lucky enough to be able to hear her tell her life story, on the oral history tapes she recorded in 1982.

I wrote an abridged summary of those tapes for an Asian Studies class I took (where the teacher was kind enough to let me fudge the definition of “Asian immigrant”). I’m sharing it here so that others can hear her amazing journey. I’m proud and amazed to be part of her legacy.

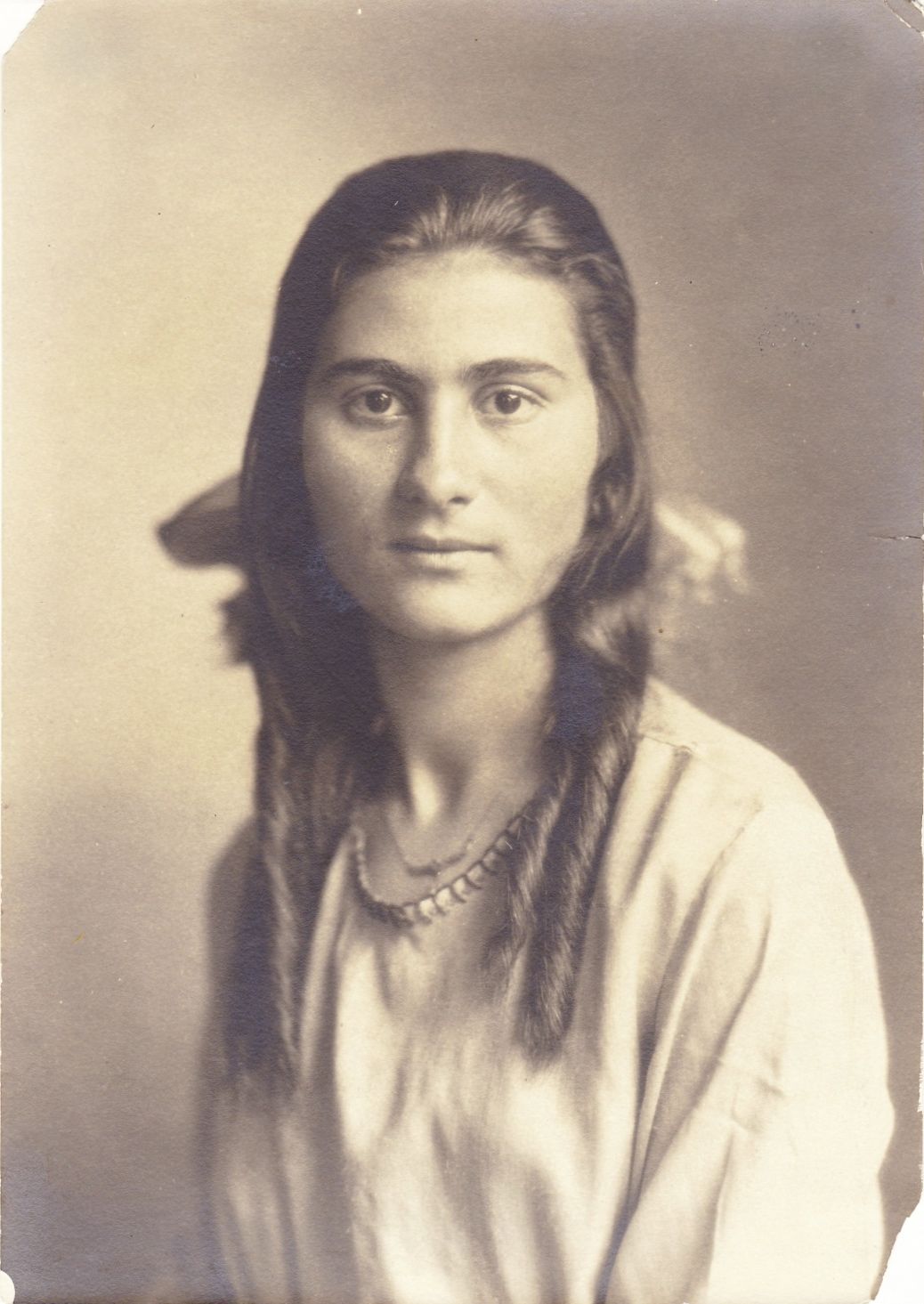

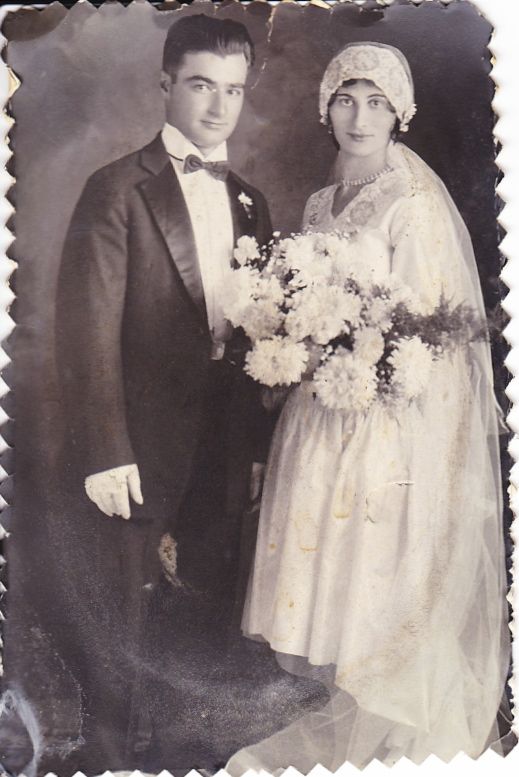

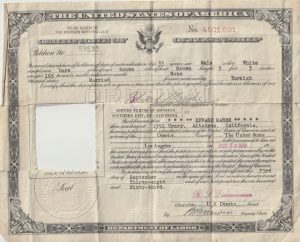

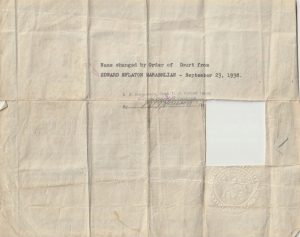

Alice Marsh’s (nee Aroosiag Samercashian) Journey to America Abridged Summary of Oral History Tapes, compiled and analyzed (with additonal material added) by Jenee Hughes, February 3, 2011 Aroosiag Samercashian’s first memory was of bullets. Hadjin, the remote mountain village that she lived in, was under siege by Turks whose goal was to murder all the Armenians in the town. Her mother was combing her hair in the American orphanage they had taken refuge in, when a bullet landed at her feet. It was just the beginning of an incredibly arduous journey, which would eventually lead her and her family to America. In 1982, seventy-three years after that, Aroosiag (now named Alice Marsh and living in Pasadena, CA) would recount the story of her life and her journey to America to a CSUN student taking an ethnic studies class, recording it on tape for posterity. Aroosiag Samercashian was born in 1906, an ethnic Armenian in the highlands of Cilician Armenia. Her father was an assessor who worked for the government, and her mother was a teacher, employed by American missionaries in their hometown. Both parents were from Hadjin, a “resort town” in the mountains, far from any sort of industrial work. Her mother lived in Hadjin with the children, but her father had to live and work in the city. In 1908, the Young Turks and some Armenian revolutionary groups overthrew the Muslim sultan of Turkey and the Ottoman Empire in a bloodless revolution. They attempted to establish a constitutional government, though the regime never stabilized. As part of this government, though, for the first time, the predominantly-Christian Armenians were allowed to own guns. Muslim Turks were uneasy about this, so when the former sultan called for a coup to regain Turkey for Islam in April 1909, they were more than willing to oblige. Masses of ethnic-Turkish Muslims descended upon towns in Cilicia, burning villages and showing no mercy to any Armenians they found. Many villages were wiped off the face of the map in a matter of days[1]. In Hadjin, there were some American missionaries who refused to leave the town, one of whom eventually wrote and published a firsthand account of their experiences. The Turk’s fear of the repercussions of killing Americans, combined with the steadfast resistance provided by the men of Hadjin, protected the town to some extent. The invaders were never able to breach the town wall, but they threw torches at thatch roofs to burn down buildings, and shot anyone they could. The villagers telegraphed for help, and finally, after a week of siege, during which all the water sources into the town were dammed and all communication wires cut, a regiment of the Young Turk army came to stop the carnage. The resident Turks of the town were appointed by the army to be a police force. Under their idea of justice, all able-bodied Armenian men in the town were arrested and put into the dungeons of Crusader-era castles[2]. One of these men was Aroosiag’s uncle, who, after three years in the dungeon, was released, and went to America. He would eventually be her sponsor to travel to America. After the siege, life in Hadjin continued. From age 4 to 7, Aroosiag went to the American Protestant School, which was taught in Armenian, by Armenian teachers. When she was 7, the Turkish authorities shut down the school. , an American Missionary who was running the school, questioned the Turks on why they were doing this. According to her memoirs, they replied, “You can tax and re-tax an illiterate Armenian and impose upon him as one chooses. He sighs but cannot help himself and one can do as he pleases. Educate this same man and when thus treated he asks for an explanation or proves that this is unjust.” [3] In 1914, rumors reached Hadjin of the huge war starting in Europe. The American missionaries left Hadjin, to return to America, deciding that the threat of WWI erupting nearby was too much for them. In 1915, the Turkish gendarme (police) started deporting the Armenians who survived the Hadjin Massacre. In September of 1915, when Aroosiag was nine, it was her family’s turn to be deported. Her father had survived the massacres in the city where he lived, and was being held for deportation there. Her family was told to bring everything they owned—but only what they could transport on foot to Aleppo, Syria—over 200 miles away, through the desert. Possessions that were deemed too valuable were taken by the gendarme for “safekeeping”. (Her mother, who was a wedding-dress seamstress, saved all her good cloth by stuffing it into the mattress they took with them.) Their house was boarded up, and Aroosiag, her mother, and her sister (Miriam) began to walk. The journey through the desert started in September, and ended in January 1917. They went through many places where there was no water. Many people died of starvation or dehydration. At one point, Aroosiag herself almost died from dehydration. Her mother went begging for water from the rich Armenians, who had carts to carry things, offering everything she owned just for water. They turned her down, because they didn’t have enough for themselves. She was saved when they happened upon a muddy puddle, which they filtered with a cloth. Every evening, at 5 or 6 o clock, her family would put up their tent (which they also had to carry all day). They had no men, so they had to do it all themselves (Armenian families are patriarchal, leaving her family at a distinct disadvantage). They ate (if they were lucky), sang the hymn “Abide with Me” in Turkish, and went to sleep. They were woken at 5am every morning by Turkish gendarmes, who yelled, “Get up! Get up!” and knocked down the deportees’ tents. The family packed and folded their tent, getting everything ready to carry for the next day. Her mother, every night, would try to find someone from whom to rent a donkey to carry their mattress and tent for the next day. One night, she was unable to. She sent her two daughters ahead with another family to the next town, to look for someone to carry their things. The sisters arrived in Baab, Syria, and waited for their mother, but she didn’t come for days. Their mother finally showed up several days later, absolutely exhausted. She had ended up carrying everything herself: mattress and tent and everything they owned. One day on the trek, Aroosiag, her mother and her sister shared camp with people from the town where her father had been deported from. Her family had been hoping for a reunion, but everyone said they hadn’t seen her father that day. Aroosiag and her family didn’t find out until a year later that he had died in that very camp, the day before. His friends from the other town knew his family was coming, wanted to spare them any more tragedy, and buried him there before they arrived (Burial was uncommon, since deportees didn’t have the strength to spare to dig graves, but the Armenian tradition of not wanting to being the bearer of bad news overrode this[4]). Without knowing it, and without being able to say goodbye, the family spent the night next to his grave. Her mother, while in camping near Baab, discovered that her cousin had married an Arab woman, and thought she might be able to get a visa to go to their town: Sephira, Syria. She spoke fluent Turkish, and went to the government building there, masquerading as a Turkish woman to try to get a visa. The man there gave her one, and she practically ran out the door. As she ran away, he called out the door: “Lady! Lady! Come back! Come back!” She was worried he was going to take away her visa, and she continued running. When she got to camp, she looked at the paper, and realized he had forgotten to sign it. She went back, and he signed it, and they had a laugh over it. The family went to Sephira and moved in with her cousin, his Arab wife, and their two children. At this time, her mother found out that the American Missionaries who had left their village had sent money for her to Aleppo. She left Aroosiag and her sister with the cousin, and went to Aleppo to pick it up. She was successful, but caught typhus on the journey. When she arrived back to Sephira, she was almost too weak to speak. She gave the money to Aroosiag’s elder sister, and told her to keep it safe. Soon after, she was left bedridden and delusional. Her sister hid the money pouch under her mother’s pillow, figuring this was the safest place for it. She touched it every night to check it was still there it. Aroosiag and her sister played with their Arab cousins, but were not given food or water by their Arab aunt. They only got what food their Arab cousins were able to sneak away for them. Eventually, Aroosiag’s mother got better, and asked where they money was. Her sister gave her the pouch, but when they opened it, it was filled with rocks. The aunt had stolen the money, and used it to feed her children, while still not allowing Aroosiag or her sisters to have any. Though mother was still very weak, she decided it was time to leave, saying there was no place for them there. They decided to go to Aleppo, which was considered a safe haven. However, when they arrived, they found the Turkish gendarmes were deporting everyone from there too. They went to a church, but there was no place to hide there. They stood there, out in front of the church, everything they had in the middle of the street. Next thing they knew, someone came to them and said “Reverend Eskigian has an orphanage, and he is the one that helps people like you.” They went to his house, but he wasn’t home. His wife sent them to a cold room in the back of the house. They were hungry, because they had had nothing to eat or drink for a long time. They “just sat there, shivering”. The reverend had gone to Der Zor, where a million and a half Armenians had been massacred, to get the orphaned children there and bring them to his orphanage. When he came home, his wife tried to get him to eat before he went in the back room. He asked if anyone was in the room, and she said yes. He went in, saw them shivering, cold, and told his wife “You’ve got to feed those people”. They ate well for the first time in weeks. He took them to a house across the street from the church, where he was keeping some people. He offered to take children to the orphanage, but Aroosiag’s mother, having already lost a daughter in the Hadjin Massacres, didn’t want them to leave her sight. So, they stayed in the little house. Aroosiag got sick with typhus and had to be taken on a horseback ambulance to the hospital. Her mother was running behind a horse-drawn cart, trying to keep up. She came to a bridge and realized she didn’t know where she was going. According to Alice Marsh years later, her mother “heard a voice saying, ‘Who gave you this child? What are you doing?’ She stood there, and said ‘Lord, pardon me. Thy will be done’, and she turned back” to take care of her other daughter. Aroosiag was in the hospital for ten days. No one was allowed to visit. Her sister found out where she was, and brought oranges, but they wouldn’t give them to Aroosiag (The nurses took them and ate them themselves). She had an Armenian doctor, who despite many physical deformities was one of the most outstanding doctors of those days. After ten days, she was feeling better and decided she wanted to go home. The doctor agreed that she was well enough, and let her leave. She was very weak, shaking as she stood up, but began to walk to horse cart “taxis”. She stood there, shivering, and a man with a cart approached her, asking where she wanted to go. She told him, “Home.” He asked, “Where is your home?” She replied, “I don’t know, but it’s across from the church.” He asked, “What church?” She told him that she didn’t know. The man took her anyway because she promised to give him four mettalik (a denomination of currency) if he brought her to her mother. Miraculously, the man took her straight to her house. A few days later, the Turkish gendarmes found them and were going to deport them to Der Zor (where the bulk of the massacres were taking place). One of the Turkish secret servicemen (an undercover supporter of the Armenians) said that the church across the street was a good place to hide. They went into the church but didn’t know where to hide. Aroosiag’s sister noticed that a few people had gone upstairs, but never came back. Aroosiag and her family followed suit, and they found everyone hiding in a secret false ceiling/floor. When the Turkish gendarmes arrived, they couldn’t find the Armenians. The leader was banging on the walls, screaming “Where did they go? WHERE DID THEY GO? Where did they disappear!? Were they angels?! Did they fly to heaven?!” The gendarmes decided that they couldn’t have actually left the building, and decided to wait them out. Aroosiag and the sixteen other people hiding in the church eventually got very hungry. When it got dark, friends on the outside(including some Turkish friends from Hadjin) sent them bread by strings, and let them know if the guards were still there. This continued for quite some time, but eventually, the gendarmes got tired and left. They all went back to the little house and made sure there was a watchman on top of the church at all times, to ensure that they didn’t get caught by surprise again. One day, the lookout forgot to go up, and they were caught. They had to escape. Her mother sent her daughters to Reverence Eskigian’s girls’ orphanage. She did so under protest but realized it was the only way to keep her girls safe. She had a friend who was a principal of a boys’ orphanage, so she went to work there as the head cook, using her visa to masquerade as a Turkish woman. Aroosiag (10 yrs old) and her sister (15 yrs old) were in the orphanage for quite a while, until Reverend Eskigian got typhus and died. While Eskigian was president of the orphanage, the Turks couldn’t come and take any girls. The moment he died, the Germans opened the doors so that the Turks could come in and take girls. Aroosiag and her sister were out in the yard when a big wealthy Turkish man came. He pointed to Aroosiag, and said, “That is the girl I want!” (It was not unheard of at this time for Turkish families to adopt Armenian girls, raise them as Turkish, and marry them off to one of their sons). The orphanage staff told him that she had a mother, but he didn’t care: “Mother or Father, I don’t care; that is the girl I want!” He had to go get permission from someone at the boys’ orphanage, where Aroosiag’s mother was working. She caught wind of the plan but could do nothing about it. The next day, he came back with the men who could give permission for him to take Aroosiag. When they were at the front door, Aroosiag’s sister rolled her in a rug and stood up the rug in a corner. When the men entered, they couldn’t find her. The Turkish man was very angry, and they searched the whole place. He left empty-handed. Her mother, having gotten news of the near adoption, begged the boy’s orphanage’s principal to let her daughters stay with her, promising they wouldn’t be much trouble. He finally agreed. Things were fine for a time, but one day, Aroosiag was out in the yard, playing with the principal’s younger daughter, who she’d gone to school within the old country. A woman who came to the boys’ orphanage saw her and decided she wanted to adopt a girl instead. Specifically, she wanted to adopt Aroosiag. The principal couldn’t say no, because everything was under German control then. Aroosiag was very distinctive looking: she had long black hair past her waist and big black eyes. The principal’s solution to save her from adoption was to make her unrecognizable. He had four people hold down her arms and legs and shaved her head. She was screaming and crying the whole time, but when the woman came back later that day, she didn’t recognize Aroosiag. The principal told that woman that Aroosiag’s mother came and took her back, so she wasn’t here anymore. Soon, that orphanage closed too. It was a little before WWI Armistice was signed. The British had taken over a Turkish fort in Aleppo and had invited all the Protestant Christian Armenians to take refuge there. People were coming from the villages all over Syria, getting word that the war was going to be over. When Armistice was signed, they opened a school at the Protestant church where Aroosiag’s family went. Her mother wanted her to go to school, so she could become a teacher. So, she started to go to school. It was quite a walk from the fort to the church, and she had to go through an Arab marketplace, the layout of which changed almost every day. It was very dark, and a little scary, but she had to go through it to go to school One Friday, not long after school started, she got to school, but there were only two or three people there. The custodian’s daughter came in and told the children, “Go home, there is a massacre going on.” The Armenian refugees were selling their wares at a flea market, in direct competition to the Arab marketplace. This eventually sparked a riot that became a massacre. According to Aroosiag, “these Arabs … killed a thousand Armenians that day, in that market, and went into homes even,” when they knew Armenians were in there, and pulled them out and killed them. Aroosiag had to walk through the Arab marketplace to go home to the fort, which she knew would be dangerous, but she had no other choice Years later, she would recall: “As soon I got to the entrance of the downtown… I stopped. I saw blood running down, right in the middle of the street. And the Turks and these Arabs had Armenians here and there, and beating them, “Armenian! Armenian!” and killing them. So, right then and there, I said, ‘I’m not going to get to the fort’. I’m going to a friends’ house—Aigian’s, I’m going to the Aigian’s house. I had to cross the street and walk about a block or so and reach their house at the end of the street. It was not open; there was a little wall… So, I cross the street just shivering, just petrified to see if they were going to see me because they were right there! I passed there, and nobody saw me. The Lord made them blind; shut their eyes. I rushed up there, went to the door, and knocked on the door. “Who is it?” My name was Aroosiag, Morning Star, (my mother took it from the bible)… He opened the door, said “Alright!” Great big rocks, he had against the door. He pulled me in and shut the door again. That was in the morning. I stayed there until five o clock. I said, “Ohhhh, I’d better go, my mother is going to be so worried.” He said, “No, we’ll wait until all the bang-bangs gone.” So they fed me, they took care of me. I was crying. I supposed I was about 11, or a little over eleven maybe.” When all the noise stopped, they opened the door and saw British and Hindu soldiers guarding the wall that you had to climb over to get to the fort. The Aigians knew English, and taught Aroosiag her first words in English: “My mother in there!” She told the guards this, and they understood her. They took her hand and walked her up to the gate of the fort. They unbarred the door, and as it opened she saw all her family waiting for her, crying with happiness that she was alright; her mother, sister, sister’s fiancé, two aunties, all “just crying”. From there, according to Aroosiag, “things were okay”. There was an orphanage that had opened up in the capital of Cilicia. Her sister’s fiancé, Jeremiah, had been offered a job there, as had her mother. They went and lived there for two years. One day, her family received a letter, saying that the American missionaries had found out the war was over, and that they and all the Armenians came back to Hadjin. The letter said that Aroosiag’s mother could have her job back, and said to send Aroosiag there as soon as possible so that she could learn English at the Hadjin’s girls’ school. At the same time, Aroosiag’s uncle had sent them a letter, telling them to “come right over” to America. It had long been Jeremiah’s dream to go to American, and as the only male in the family, it was his decision. There were many arguments, but eventually, it was decided that Aroosiag would be traveling to America to live with her uncle and her auntie Rebekah. Her uncle, after spending three years in a dungeon for defending Hadjin in 1909, had left Armenia, correctly predicting that the worst was yet to come. He went alone to Argentina, South America, then emigrated to Syracuse, New York in 1914. He was one of 6533 Armenian men and 7785 Armenians of any gender to enter the United States during that year. When in New York, he sent for his immediate family to join him from Armenia. If my calculations are correct, they arrived in 1915, leaving Hadjin just before the deportations. In 1915, only 982 Armenians entered the United States, since most Armenians in Turkey were actively prevented from leaving the country. This is apparent when you realize that Armenian immigration dropped 83% from 1914 to 1915[5]. The immigration numbers would remain low in 1916 (only 964 Armenians), 1917 (only 1221 Armenians), 1918, (only 221 Armenians), and 1919 (only 282 Armenians) [6]. In 1916, they all moved to Pasadena, California. He had six children: Harrem, Agnes, Florence, Dan, and Sam, and Robert. Agnes had had a twin sister, Alice, who had died before they went to America. When Aroosiag came over in 1920, he said, “Your name is no longer Aroosiag, it’s Alice, and you’ll be my new daughter now”. Aroosiag was one of 2,768 Armenians who came to America in 1920, a year before immigration quotas were established by the “Three Percent” Immigration Law in March 1921. This law said that the number of immigrants to the United States between June 3, 1921 and June 30, 1922, could not exceed 3% of the immigrant population from any given country, as counted by the census of 1910. No provisions were made for refugees, so this meant that only 2,757 Armenians could come during that time[7]. After that, the Armenian borders opened up, but immigration into the United States was restricted (which I’ll go into a few paragraphs). She arrived at Ellis Island after taking a boat to America. Aroosiag (from here on out referred to as Alice) was incredibly seasick and had a particularly thorough medical examination, but she was found healthy enough to enter the country. She hopped on a train and arrived in Pasadena the day after Christmas: Sunday, December 26, 1920. She was fourteen years old. Her aunt and uncle had gotten her lots of presents to open, and were so excited to see her. Her cousin Agnes was singing on the corner when she arrived, a song that she’d learned from the evangelical preacher who had just visited. Agnes, like the rest of her siblings, spoke little to no Armenian. Alice spoke no English, but she learned the song, and they both sang together. The day she arrived, she went to Sunday school at Lake Avenue Congregational Church, attending the 15-year old girls’ class with her cousin (even though she was fourteen). She would attend that church until the day she died, but as a teen, she slao went to the local Armenian church to attend an Endeavor Class. Her mother immigrated the year after Alice did, with Alice’s sister’s family in tow (consisting of her sister, Jeremiah, and their newborn baby). They arrived in Pasadena on December 30, 1921. They were part of a huge flood of Armenian immigrants: 10,212 Armenians entered the country during 1921, and at least 8000 of those arrived after the 3% Quota Law expired in August[8]. Her brother-in-law, Jeremiah, had said, “Even if I die, I want to go to America”. His body was taken out of the house on January 30, 1922. He was 24 years old and had been in the country for less than a month. Her sister was left widowed with a baby at age 22. Their uncle had borrowed $2000 from the bank to bring them over. Like the Armenian immigrants we read about in “Our Oriental Agriculture”, he had been “pretty thoroughly fleeced…by the banks” (pg 121), who gave him an unreasonable payment schedule. Everyone in Alice’s family had to work to make money to pay them back in time. Her mother went and stayed with a woman who needed someone to take care of her. Alice worked as a mother’s helper, and her sister worked as a housekeeper. They all found their jobs through the church. At one point, they had paid off $1300 of the debt, but had $700 left, and the deadline was drawing close. They didn’t know what they were going to do. There was an immigrant Armenian man who came on the same boat as her mother and sister, and “couldn’t get over how people could love each other like her family did”. When they left the boat, the man asked them to write, because he wanted to stay in touch. Things got busy, and they never got the chance to write. He tracked them down, and wrote them, saying that they lied because they said they would write. Her mother wrote back a letter, apologizing and explaining that since Jeremiah had died, they hadn’t had the chance to write. He wrote that he wanted to come to them to help. He was a bachelor, and very much wanted to join their family. Alice’s sister wrote back, saying that he shouldn’t come if he was just coming for her, but that California was a lovely place, and that he should come for California if he wanted to. They continued writing back and forth for about two years, and he came to Pasadena to ask Alice’s sister to marry him. She accepted, and he paid the $700 they owed. From the moment she arrived in America, even before the rest of her family arrived, Alice was very, very excited to go to school and learn English. However, she noticed that her aunt and uncle were speaking English “kind of funny” when the children were talking together, it was a different English. She told her uncle she wanted to be in the first-graders’ class, because she wanted to learn good English, not “street” English. He accepted her request and sent her to the neighborhood school (Longfellow’s school), where she towered over all the seven-year-olds in her class. Dr. Hettson, the principal of the school, came to her uncle and said that it wasn’t fair to her and the smaller children for her to be in that class. So, they sent her to a school for the “backward children”: Wilson School at the corner of Morongo and Walnut. There were “great big boys and there; colored, black”. She remembers one black girl named Baisy, one Mexican girl named Lucy, and many white girls even bigger than her. Her teacher, Miss Rude, was a “great big fat teacher”. However, in the three months that Miss Rude taught her, she reached the 5th grade level, and was able to transfer back to Longfellow. At Longfellow school, they placed her in 6th grade; but she soon skipped 6th grade to go to 7th. For seventh grade, she went to junior high at Marshall Jr High, also known as John Muir Jr High and Wilson Jr High, at the corner of Walnut and Las Robles. She went to school until the 9th grade when her mother got sick. From that point on, she started working in the home, and eventually met an Armenian man, who she met at the local Armenian Church’s Endeavor class, named Edward Marsh (formerly Marashlian). (Editors Note: We recently found the documents where Edwards’s name was changed as he became a US citizen on Sept 23, 1938. A picture was part of the original document but it has been cut out. ) They got married and had four children, one of whom was my grandmother, Joyce Agnes Campbell (nee Marsh). Alice Marsh died just a few months after I was born in 1987. Hearing her story via oral history tapes, I’ve got a much better grasp on how difficult it was to immigrate here, but also understand how many opportunities America offered her. Her story is rather unique in that she never had a country to go back to (Reports that Hadjin had been reclaimed by the Armenians were false, and if they’d gone back there, they would have been unwelcome). America immediately became Alice Marsh’s home, and the hardships she and her family endured here allowed them not only to live a better life, but to have a life at all. Note: The two-part Nana Oral History recordings are on these pages:

[1]Terjimanian, Hajop; “Californian Armenians: Celebrating the First 100 Years”; published in 1997 [2] Lambert, Rose; “Hadjin, and the Armenian Massacres”, published in 1911 [3] Lambert, Rose; “Hadjin, and the Armenian Massacres”, published in 1911 [4] Vartan, Malcolm; “The Armenians In America”, Published 1919 [5] Vartan, Malcolm; “The Armenians In America”, Published 1919 [6] Yeretzian, Aram Serkis; “A History of Armenian Immigration to American with Special Reference To Conditions In Los Angeles”; Published as a USC graduate thesis in 1923. [7] Yeretzian, Aram Serkis; “A History of Armenian Immigration to American with Special Reference To Conditions In Los Angeles”; Published as a USC graduate thesis in 1923. [8] Mahakian, Charles; “History of the Armenians In California”, Published as a UCB graduate thesis in 1935. |

Comments

Alice Marsh – Oral History — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>